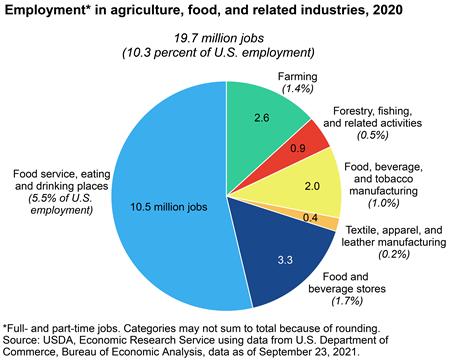

Figure 1 (11)

In the past, agriculture has always been associated with expansive fields, roaming livestock, and large machinery. This stereotype exists for good reason—throughout history, farming has been a rural practice, involving tilling fields, driving large tractors, and monitoring acres of land. In many regards, this rural type of farming has been successful. Economically speaking, for example, farms in the United States contributed 134.7 billion dollars to the GDP in 2020, making up 0.6% of the year’s gross domestic product, which is more substantive than you may think considering that the GDP is made up of everything we consume; export; make in business investment, real estate, and finance; and also what the government spends (11). On top of this, as illustrated in Figure 1—created by the United States Department of Agriculture—the practice of farming employed 2.6 million people in 2020 (11).

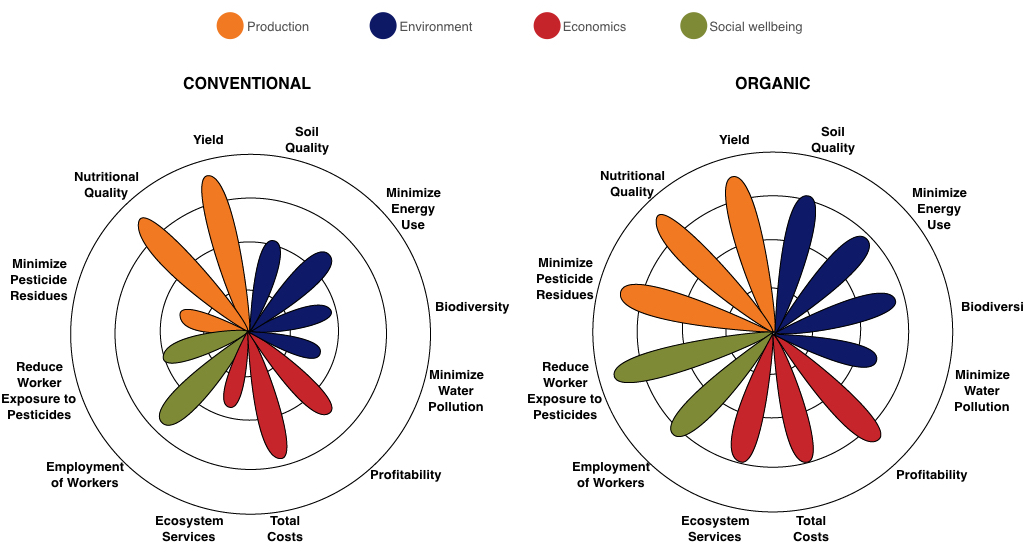

Comparing Conventional and Organic Farming

Figure 2 (19)

Under the umbrella of rural farming exists two different types: organic and sustainable farming, and conventional farming. Figure 2, pictured to the left, is a visual representation of the similarities and differences between organic and conventional farming. It breaks conventional and organic farming down into different components by color-coordinating them: the orange portions of the graphic are related to production, the blue portions are related to the environment, the red portions are related to economics, and the green portions are related to social well-being. The longer the graphic extends to a particular component, the more it is prioritized. Conventional farming, for example, prioritizes yield and does not put much effort into maintaining soil quality. In general, as displayed in Figure 2, organic farming involves a much more holistic approach to farming, whereas conventional farming prioritizes some components more than others. Looking at the production section of Figure 2, for example, minimizing pesticide residues on crops is seemingly unimportant to conventional farmers, who instead focus on maximizing the nutritional quality and yield of their crops.

Image 1 (24)

As seen in Image 1, large-scale conventional farmers drive chemical-spraying tractors over their fields, drenching every crop in pesticides. The reason for this is that conventional farmers use pesticides and fertilizers to improve the efficiency and size of their crops, providing larger yields and shortening the amount of time they need to grow. These pesticides, though, often contain carcinogens that are toxic to consume, and that deteriorate soil quality. Considering that most people incorporate vegetables into their diets for their nutritional value, it makes no sense that these vegetables should be harming us more than helping us, exposing us to cancer-inducing, and artificial chemicals. The environment section of Figure 2 is also worth pointing out, as it is clear that conventional farmers do not put nearly as much effort into components like soil quality and biodiversity compared to what organic farms do. The ramifications of conventional farmers’ lack of commitment to the environment, specifically soil quality and biodiversity, loom large. Karen Perry Stillerman, deputy director of the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, stated in an interview that “when soil is healthy, it can hold a lot more water and drain better, but it also can be part of the climate solution.” Microorganisms that are capable of sequestering carbon and absorbing it back into the ground thrive in healthy soil, meaning that healthy soil is not only beneficial to water drainage and crop health, but also to the reduction of atmospheric carbon.

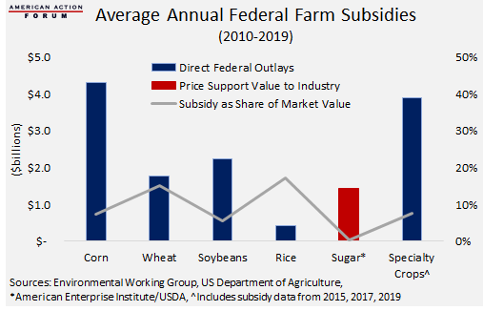

How Does the Government Influence Agriculture?

Figure 3 (20)

As highlighted in Figure 2, all evidence supports that conventional farming is not as environmentally friendly as sustainable farming. However, the US Government not only condones but incentivizes conventional farming. It does this by subsidizing certain crops, which basically means that it rewards farmers with capital for harvesting specific crops that are in demand. Figure 3, for example, illustrates farm subsidies from 2010-2019 for corn, wheat, and soybeans—as the figure shows, all three of these crops have been backed by over two billion dollars annually in government subsidies. This large amount of capital dedicated to specific crops causes farmers to devote entire fields to growing the subsidized crops, putting all of their energy and resources into what will make them the most money the fastest. Though this is economically efficient, when entire fields are all made up of the same crops, farms risk extinction. Uniformity amongst the crops is inherently dangerous, as it means no biodiversity. Looking at the human species as an example, if we were all genetically modified to be the same as these conventional crops are, one specific pathogen would have the ability to wipe us all out. However, since we all have different genetic makeups, we have different immunities, meaning that one virus or pathogen will not be able to kill us all off. Where sustainable agriculture is more centered around building regenerative ecosystems with thriving biodiversity and soil health, conventional farming is focused on efficiency, and maximizing the yields of harvests by any means necessary, with little regard for any environmental damage done.

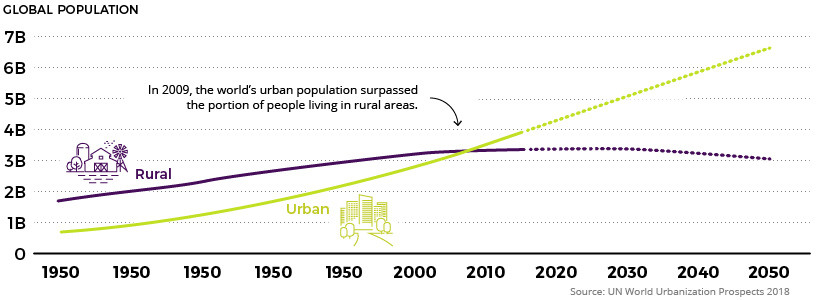

Is Rural Agriculture Really Sustainable As We Look Into The Future?

Figure 4 (23)

From an environmental and climate standpoint, sustainable rural agriculture is a far healthier alternative to conventional farming. It is less intrusive and with less energy input than conventional farming, featuring hands-off and chemical-free techniques that in turn lead to thriving soil which can absorb atmospheric carbon and reduce climate change. But sustainable rural agriculture isn’t perfect, either. Why? Well, it is not because of any technical issues involving farming techniques—instead, it stems from people wanting to live in cities. As portrayed in Figure 4—which the United Nations World created to highlight the increasing urbanization going on worldwide—in the past, rural living was a popular, sought-after, way of life for people. Now, though, and as we look into the future, people are settling in cities at an increasingly fast rate.

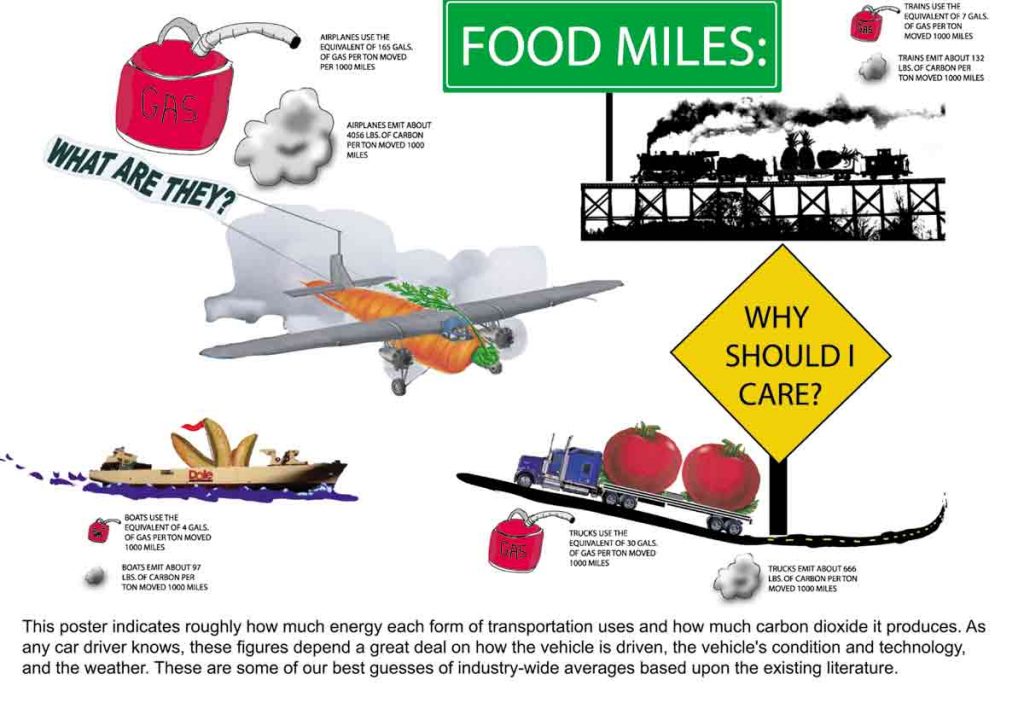

Figure 5 (21)

Because of the rapid urbanization of society, even the most sustainable rural farms have larger carbon footprints than what is healthy in the long term. This is because, once all of the produce is harvested on rural farms, it oftentimes has to be transported long distances to the cities in which the majority of society lives. For example, according to a study highlighted by “The Conscious Challenge,” which is a campaign for heightened awareness and change of our current environmental footprint regarding food and clothing transport, “western society routinely purchases food that was grown more than 1000 miles away and transported to the local grocery store (21).” This distance, though, only tells a portion of the story when it comes to determining carbon emissions from food transportation. As illustrated in Figure 5, which is a visual representation of how much carbon is emitted per ton of produce transported 1000 miles published by the Hawthorne Valley Farmscape Ecology Program, carbon emissions vary greatly depending on the mode of transportation. For example, airplanes emit around two tons of carbon per ton of produce moved 1000 miles and trucks emit 666 pounds of carbon as well, whereas boats only emit around 97 pounds of carbon (21). To put these numbers in perspective, flying produce from a rural agricultural hub like Iowa across the country to the city of Boston, Massachusetts, would leave a larger carbon footprint than shipping produce from the United States to Asia via a cargo ship. According to The Conscious Challenge, though, due to sea shipping being so slow and fresh produce having a very short lifespan after being picked, “food is increasingly being shipped by faster—and more polluting—means” such as airplanes and trucks (7). As a result, “it is estimated that we currently put almost 10 kcal of fossil fuel energy into our food system for every 1 kcal of energy we get as food” (7), meaning we put ten times more energy into our food than we get out from it.

What Can Be Done To Reduce Food Miles?

To reduce the carbon footprint of agriculture in the US to a sustainable level, mitigating conventional farming practices and switching to sustainable rural farming is clearly not enough on its own, as food miles are still responsible for emitting a significant amount of the carbon footprint of the food. Instead, we need to look towards ways to implement urban agriculture within our growing metropolises, supplementing sustainable rural agriculture and providing more local produce to our city dwellers.

So What Is Urban Agriculture In The First Place?

Image 2 (25)

Image 3 (15)

Image 4 (26)

Urban agriculture involves the cultivation and distribution of many different crops in urban areas. In general, urban farms exist on rooftops, as rooftops are oftentimes the largest plots of land in cities that are unused, flat, and available to farm on. Underneath the umbrella of urban rooftop agriculture exists many different types of farms, ranging from community gardens, portrayed in Image 2; to greenhouses, shown in Image 3; to open-air farms, illustrated in Image 4, and more. These different types of farms are chosen by farmers for different reasons. Community gardens, for example, often act as community centers, serving as spaces where people can gather around together and grow their own organic food, building leadership and teamwork skills in the process, whereas rooftop greenhouses often serve as large-scale, commercialized, for-profit farms that do not disrupt businesses or residents below them (4).

Now, let me pause for a second and make something clear before I get into the nitty-gritty details about urban farming and what it has the potential to look like in the future. I am not arguing that rural sustainable farms are bad. Clearly, as highlighted in the statistics mentioned in Figure 1, all farms are integral to the economics of the United States, and on top of their capital-based value, without the production from rural farms, urban farms will never be able to provide enough produce to feed all of society. Instead, I am arguing that urban agriculture needs to increase production so that rural farms are not tasked with providing cities that are thousands of miles away with all of their produce. If we efficiently invest time and money into urban farming, it is not unfathomable to look ten, twenty, or thirty years into the future and see urban agriculture supplying cities with substantial amounts of produce—especially those foods which perish quickly or lose their nutrient content by being picked too early to ship.

Image 5 (9)

For example, one of the leading urban farming organizations that I will dive into later in this blog—Montreal, Canada, based Lufa Farms—supplies 2% of Montreal’s inhabitants with fresh produce, but they are optimistic that it will provide close to the entire city with their locally-grown produce in the future (9). As seen in Image 5, their greenhouses are incredibly large scale, and they are for good reason as they continually push to grow as an organization, feeding more people nutritious food and profiting as a result. In an interview with Fortune, co-founder of Lufa Farms Mohammed Hage emphasized “our objective at Lufa is to get to the point where we’re feeding everyone in the city” (9). Currently, most urban supermarkets’ produce sections in the United States are filled with rural-grown vegetables, but as we look into the future, at least a portion of these vegetables will continue to get replaced by urban, locally-grown produce by organizations like Lufa.

On top of Reducing Food Miles, What Else Does Urban Agriculture Help With?

Image 6 (27)

As mentioned earlier, one of the largest issues of rural farming is a large amount of carbon it emits due to food transportation from rural areas into cities. Localizing our produce and reducing our food miles and carbon emissions are not the only benefits that come with implementing sustainable urban agriculture. For one, fruits and other produce items that are shipped long distances often have to be picked prematurely to ensure they do not go bad by the time they arrive at stores. The Conscious Challenge, for example, illustrates that produce often has to be picked prematurely if it has to travel long distances before being sold: “In order to transport food long distances, much of it is picked while still unripe and then gassed to “ripen” it after transport, or it is highly processed in factories using preservatives, irradiation, and other means to keep it stable for transport and sale” (7). Looking at Image 6, which is the banana displays bananas for sale at Whole Foods market. All of the bananas were picked prematurely, illustrated by the fact that the bananas are green as opposed to the ripe yellow that the bananas should be.

Image 7 (28)

Along with helping to mitigate the need for premature picking, and increasing the locality of produce, sustainable urban agriculture also has the potential to conserve water resources at a much higher rate than rural farming does. According to the World Bank, “Currently, agriculture accounts (on average) for 70 percent of all freshwater withdrawals globally,” playing an enormous role in water scarcity issues (16). However, according to the National Park Service, “hydroponic systems use less water — as much as 10 times less water — than traditional field crop watering methods (10).” The way it can do this, is through technology available in rooftop greenhouses known as hydroponic systems. These hydroponic greenhouses conserve water by collecting rainwater, recycling it and adding nutrients to it, storing it in large tanks, and reusing it. As seen in Image 7, which highlights the inside of a hydroponic rooftop greenhouse, hydroponic systems are soilless. As a result of this, water never enters any soil, and therefore also never evaporates, allowing it to be recollected and reused repeatedly. On top of conserving water, the soilless approach to the hydroponic system in the rooftop greenhouses also helps to reduce the 4 billion tons of topsoil that erode on rural farms every year due to tilling practiced, creating runoff and other environmentally damaging consequences (15).

Hydroponic Systems Versus Soil Systems: A Comparison of Urban Rooftop Farms

Image 8 (34)

There is much speculation about the nutrient-richness and overall quality of hydroponically grown produce in comparison to traditional, soil-based, farm systems. Many people believe that the abundance of microorganisms and organic matter in soil inherently makes traditional, soil-grown, crops more nutritious than soilless hydroponic crops, which are without said microorganisms and organic matter. In response to this hypothesis, Ohio State University conducted a study examining the differences between growing lettuce in a hydroponic system versus growing lettuce in organic soil. Interestingly, the study found that “hydroponic lettuce had higher amounts of amino acids (protein building blocks) than the soil-cultivated lettuce. On the other hand, lettuce grown in soil contained more sugars and compounds that contribute to taste and possible health benefits, such as sesquiterpenes (which reduce harm by microbial attacks) and organic acids” (30). Evidently, there are tradeoffs between hydroponic and organically grown foods, with neither system appearing to be significantly healthier than the other. It is worth noting, though, that in this study, the hydroponic lettuce received almost 3x the fertilizer compared to the lettuce in the soil, which may be why the hydroponic lettuce had a higher amino acid count than the soil-grown lettuce did. However, this is not necessarily a negative thing: since nutrients and fertilizers are manually added to the water-based solutions in hydroponic farms, it is very easy to control both the amount type of nutrients and fertilizers that go into the hydroponic solutions that the crops are grown in, meaning that it is possible to create very efficient solutions that lead to quicker growth and more nutritious crops than soil-based systems. In sum, though it may require a larger amount of nutrients and fertilizers to ensure high-quality nutrient density in hydroponic systems, hydroponic systems still have the ability to equal and even surpass the nutritional quality of soil-based produce.

Hydroponic Rooftop Greenhouses: The Best Form Of Large-Scale Urban Agriculture?

Image 9 (29)

As hydroponic rooftop greenhouse systems are very effective at conserving water, have the ability to provide adamant nutrients to crops, and are climate controlled, urban rooftop greenhouses are clearly appealing, but they are not the only form of rooftop agriculture that is popular with the public. In fact, there is plenty of public discourse surrounding which forms of rooftop urban farming we should focus on developing as we move into a new age of agriculture. One study headed by Dr. Francesco Orsini—an associate professor at the Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences at the University of Bologna, Italy who also serves as an FAO-UN consultant in urban agriculture projects in Asia, Latin America, and Africa—delved into a metadata analysis of 185 publicly accessible cases of rooftop agriculture around the world. He and many colleagues examined the pros and cons of open-air rooftop farms and gardens versus enclosed rooftop greenhouses, attempting to discover the most efficient method of rooftop agriculture.

Image 10 (31)

Of the 185 cases, 84% were from open-air farms and gardens, meaning only 16% were from rooftop greenhouses (5). Such a large discrepancy insinuates that open-air farms may be more efficient, or may produce larger yields than protected systems like greenhouses. However, rooftop greenhouses produced an average yield of twenty-eight kilograms per square meter annually, whereas open-air systems reported an average yield of six kilograms per square meter annually, proving that rooftop greenhouses yield higher harvests on average than open-air gardens and farms. One of the main reasons that rooftop greenhouses produce such high yields is due to the fact, as displayed in Image 9 highlighting the inside of a hydroponic greenhouse, these greenhouses are able to stack rows of growing crops on top of each other, creating plentiful available space for growth. Conversely, open-air systems such as the one in Image 10, a 6,000 square-foot rooftop organic vegetable farm located in Brooklyn, New York called Eagle Street Rooftop Farm, are typically limited to the ground for growing their crops.

Image 11 (35)

Dr. Orsini’s study also compared the average water usage of hydroponic rooftop greenhouses with open-air systems, finding that “a closed-loop system in a soilless rooftop greenhouse can use 40% less irrigation water and 35–54% less nutrients per day than an open-loop system rooftop greenhouse” (5). This is significant, remembering that seventy percent of current freshwater withdrawals are due to agriculture (5). In an attempt to mitigate the amount of water lost on open-air farms, some open-air farmers are implementing systems known as drip irrigation, pictured in Image 11. The way that these drip systems work is by slowly dripping water, fertilizers, and other nutrients down into the root zones of growing vegetables via tubing. The tubing allows for far greater accuracy than other ways of watering crops, meaning that water can be applied much more evenly to crops in fields. As a result of this, irrigation does not have to run for as long to wet entire fields, saving water. According to a study done by the University of Massachusetts, “a properly installed drip system can save as much as 80% of the water normally used in other types of irrigation systems (32).” As backed by the evidence from Dr. Orsini’s study, hydroponic rooftop greenhouses are the best option when it comes to conserving water, however for open-air rooftop farmers, drip irrigation is the next best thing.

Case Studies: Looking At Two Of The Most Promising Urban Greenhouses:

The market for commercialized rooftop urban greenhouses is beginning to build momentum, especially when looking at temperate environments. Lufa Farms, a Montreal-based company, and Gotham Greens, a New York-based company, have both built commercial, large-scale urban rooftop greenhouses, and are already profiting from their investments.

Montreal-Based Lufa Farms:

Image 12(6)

Montreal-based Lufa Farms was founded by Lauren Rathmell and Mohamed Hage in 2009. They now have four urban farms, all in rooftop greenhouses featuring hydroponic systems, with the largest one measuring over 15,000 square meters and producing more than 11,000 kilograms of food every week. As stated earlier in the blog, Lufa Farms currently feeds 2% of Montreal with its produce (17). Though this number may sound small, they harvest enough vegetables each week to feed 20,000 families (6). They grow one-hundred varieties of vegetables and herbs year-round and do not use any pesticides on their produce. Their objective, as cofounder Mohamed Hage puts it, is to “get to the point where [they’re] feeding everyone in the city” (9). From an economic standpoint, the company has been profitable since 2016, highlighting the capital potential of commercialized urban rooftop greenhouses. On top of this, Lufa Farms prides itself on its energy-conserving methods and sustainability. As Lufa Farms spokesperson Thibault Sorret explains, “the advantage of being on a roof is that you recover a lot of energy from the bottom of the building,” making for sizable savings in heating, which is very important in harsh winter months in Quebec. On top of saving energy by recovering heat from the building that the greenhouse is built upon, Lufa has also worked on electrifying its fleet of delivery trucks as it is attempting to export its model on a more international scale (6).

Lufa Farms, though, has faced its fair share of backlash, specifically from smaller-scale farmers who feel as though they are being ushered out of the agricultural market by a large corporation. One farmer reflected that breaking into the Montréal market could be particularly difficult for new producers, due to large competitors like Lufa Farms: “It’s possible, you can do it, but having large players with a lot of money who can appeal to a really large mainstream population is cutting down on the people we have access to” (18). Other farmers are upset with the fact that Lufa Farms is perceived by the public as “organic,” when in reality, it is not. Another farmer noted that “people think Lufa is organic and local. Lufa gets grouped in with us and doesn’t make it super clear that they aren’t organic. They don’t say that they are organic, but they say, ‘We are sustainable, have sustainable pest management…’ and so forth” (18). Local farmers who pride themselves on being organic feel as though their market is being intruded upon by Lufa, who, quite simply, is not organic. However, Lufa Farms not being “organic” is only a technicality. The only reason Lufa Farms is not considered to be “organic,” is because “organic” crops must be grown with soil, and since Lufa Farms uses a soilless hydroponic system, even though it does not use pesticides and chemicals, it does not fall under that category.

New York City-Based Gotham Greens:

Image 13 (8)

New York-based Gotham Greens has a similar model to that of Lufa Farms. Founded by Viraj Puri and Eric Haley, Gotham Greens rooftop greenhouses are climate-controlled, growing vegetables year-round. Economically speaking, Gotham Greens has achieved a 28% year-over-year growth rate (8). As with Lufa Farms, they employ a unique hydroponic system, limiting pollution and waste, and saving land, water, and energy. Because of their proximity to such dense urban populations in Brooklyn, Queens, Chicago, and more, they can ensure less fuel consumption and associated emissions and can get their greens to their endpoints faster, meaning fresher, more nutrient-dense, better tasting, produce.

Gotham Greens currently owns one of the largest rooftop greenhouses in the world, which is located in Chicago with an area of 75,000 square feet (8). Regarding further growth, though, cofounder Viraj Puri sees no reason to slow down: “Building on the continued growth and momentum that Gotham Greens has sustained over the past several years, we are proud to bring our national brand of sustainably grown salad greens and herbs [..] to more consumers across the country and expand our retail and foodservice distribution in existing markets. Our goal is to deliver Gotham Greens’ fresh produce within a day’s drive from our greenhouses to 90% of consumers across the U.S., and these strategic greenhouse expansion projects bring us closer to this milestone” (8). Gotham Green recently opened a greenhouse in 2021 in California, for example, where more than 37 million people are affected by drought with 87% of the state classified as Severe or Extreme Drought (8). Because of its unique hydroponic growing system, its greenhouse farm has been able to save 95% more water and use 97% less land in comparison to traditional, conventional methods (8).

Looking Towards The Future Of Urban Agriculture:

Looking into the future, we can be reassured by Gotham Greens and Lufa Farms as current evidence that rooftop urban greenhouses can be effective, sustainable, and economically advantageous. On FreshDirect, for example, which is an online marketplace for fresh produce, Gotham Greens butter lettuce costs $4.49 per package (32). One of Gotham Greens’ main competitors, rurally located Organicgirl LLC, sells their own butter lettuce for $4.99.

Image 15 (32)

Gotham Greens is not only competitive in the market, but it is even cheaper than one of its main rural rivals in Organicgirl, highlighting its affordability in the produce market. However, if more companies, investors, and environmentally passionate people do not take action and begin building more commercialized rooftop greenhouses, we will struggle to sustainably feed urban dwellers and will jeopardize the future of our climate. According to a report released by the United Nations, “the world will need 70 percent more food, as measured by calories, to feed a global population of 9.6 billion in 2050” (33). We can either try to increase our food production by implementing more conventional farming techniques mentioned earlier in the blog like spraying intrusive chemicals and pesticides onto fields of uniform crops and then sending them thousands of miles across the country from rural areas to cities, or we can invest in large-scale commercialized rooftop urban agriculture, localizing city-dwellers’ produce, reducing carbon emissions, and saving water in the process.

Works Cited

(1) Buscaroli, E., Braschi, I., Cirillo, C., Fargue-Lelièvre, A., Modarelli, G. C., Pennisi, G., Righini, I., Specht, K., & Orsini, F. (2021, March 18). Reviewing chemical and biological risks in urban agriculture: A comprehensive framework for a food safety assessment of City Region Food Systems. Food Control. Retrieved October 2, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956713521002231

(2) FinancialNewsMedia.com. (2021, September 28). How urban solar greenhouses are contributing to urban environmental, Social & Economic Sustainability. Cision PR Newswire UK. Retrieved October 2, 2022, from https://www.prnewswire.co.uk/news-releases/how-urban-solar-greenhouses-are-contributing-to-urban-environmental-social-amp-economic-sustainability-835196172.html

(3) Monica, A., MacDonald, G. K., & Turner, S. (2021). Growing pains: Small-scale farmer responses to an urban rooftop farming and online marketplace enterprise in Montréal, Canada. Agriculture and Human Values, 38(3), 677-692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10173-y

(4) Archambault, S. J. (2011). Urban Farming and Gardening. In B. W. Lerner & K. L. Lerner (Eds.), In Context Series. Food: In Context (Vol. 2, pp. 785-789). Gale. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX1918600237/GRNR?u=bucknell_it&sid=bookmark-GRNR&xid=da609914

(5) Appolloni, E., Orsini, F., Specht, K., Thomaier, S., Sanyé-Mengual, E., Pennisi, G., & Gianquinto, G. (2021, February 28). The global rise of urban rooftop agriculture: A review of worldwide cases. Journal of Cleaner Production. Retrieved September 19, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652621007769

(6) (2020, August 26). World’s biggest rooftop greenhouse opens in Montreal. Phys.org. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://phys.org/news/2020-08-world-biggest-rooftop-greenhouse-montreal.html

(7) Club, M. T. C. (2019, May 21). Food & Transportation. The Conscious Challenge. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://www.theconsciouschallenge.org/ecologicalfootprintbibleoverview/food-transportation

(8) Our story. Gotham Greens. (2021, December 10). Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://www.gothamgreens.com/our-story/

(9) Fleming, S. (2021, April 20). Feeding a city from the world’s largest rooftop greenhouse. World Economic Forum. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/04/world-largest-rooftop-greenhouse/

(10) Hydroponics: A better way to grow food (U.S. National Park Service). National Parks Service. (2021, August 11). Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/hydroponics.htm#:~:text=Less%20water%3A%20Hydroponic%20systems%20use,and%20drain%20to%20the%20environment

(11) Kassel, K., & Martin, A. (2022, October 31). AG and food sectors and the economy. USDA ERS – Ag and Food Sectors and the Economy. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/ag-and-food-sectors-and-the-economy/

(12) NewYorkStreetFood. (2020, December 14). Surprising facts: Where does New York get its fruits from? New York Street Food. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://newyorkstreetfood.com/food-trends/surprising-facts-where-does-new-york-get-its-fruits-from/

(13) Sustainable Vs. Conventional Agriculture. Environmental topics and essays. (n.d.). Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://you.stonybrook.edu/environment/sustainable-vs-conventional-agriculture/#:~:text=Sustainable%20agriculture%20consumes%20less%20water,the%20integrity%20of%20the%20environment

(14) Leavens, M. (2017, March 7). Do food miles really matter? Sustainability at Harvard. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://green.harvard.edu/news/do-food-miles-really-matter

(15) About. Sky Vegetables. (2022). Retrieved October 31, 2022, from http://www.skyvegetables.com/bio-1

(16) Water in agriculture. The World Bank. (2022, October 5). Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water-in-agriculture

(17) About Lufa Farms. https://montreal.lufa.com. (2022). Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://montreal.lufa.com/en/about

(18) Allaby, M., MacDonald, G. K., & Turner, S. (2020, October 26). Growing pains: Small-scale farmer responses to an urban rooftop farming and online marketplace enterprise in Montréal, Canada – agriculture and human values. SpringerLink. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10460-020-10173-y

(19) Carmen. (2016, September 8). Strengthening Global Food Security with organic farming. Primal Group. Retrieved December 4, 2022, from https://www.primalgroup.com/strengthening-global-food-security-organic-farming/

(20) Kerska, K., & Hayes, T. O. N. (2021, November 3). Primer: Agriculture subsidies and their influence on the composition of U.S. food supply and consumption. American Action Forum. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/primer-agriculture-subsidies-and-their-influence-on-the-composition-of-u-s-food-supply-and-consumption/

(21) Food miles. Hawthorne Valley Farmscape Ecology Program. (n.d.). Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://hvfarmscape.org/food-miles

(22) Carmen. (2016, September 8). Strengthening Global Food Security with organic farming. Primal Group. Retrieved December 4, 2022, from https://www.primalgroup.com/strengthening-global-food-security-organic-farming/

(23) Ghosh, I. (2019, September 3). 70 years of urban growth in 1 infographic. World Economic Forum. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/mapped-the-dramatic-global-rise-of-urbanization-1950-2020/

(24) Ozkan, E. (2020, October 30). Best practices for effective and efficient pesticide application. Ohioline. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/fabe-532

(25) Frisbie, C. (2016, April 27). 6 inspiring urban gardens that impact the community. Mashable. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://mashable.com/article/urban-gardens

(26) Reale, N. (2021). 8 of NYC’s Rooftop Farms: Jetblue Farm at JFK, Brooklyn Grange, Eagle Street Farm, Riverpark Farm, Gotham greens. Untapped New York. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://untappedcities.com/2014/08/07/7-of-nycs-rooftop-farms-brooklyn-grange-eagle-street-farm-riverpark-farm-gotham-greens/

(27) Barnhill, F. (2012, November 16). As Whole Foods opens, Boise Co-op ready to take on the competition. Boise State Public Radio. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://www.boisestatepublicradio.org/economy/2012-11-16/as-whole-foods-opens-boise-co-op-ready-to-take-on-the-competition

(28) Staff, I. (2012, September 13). Lufa Farms plants. Inhabitat. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://inhabitat.com/lufa-farms-brings-large-scale-rooftop-farming-to-montreal/photo_2149003_resize/

(29) Dickinson, S. (2022, June 9). The world’s largest vertical farm is being built in the UK. Time Out Worldwide. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://www.timeout.com/news/the-worlds-largest-vertical-farm-is-being-built-in-the-uk-060922

(30) bilbrey.21. (2019, July 6). Hydroponics vs. soil cultivation: Functional and taste compound comparison. CEA Talk. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://u.osu.edu/ceatalk/2019/07/06/hydroponics-vs-soil-cultivation-functional-and-taste-compound-comparison/

(31) Eagle Street Rooftop Farm. (n.d.). Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://rooftopfarms.org/

(32) Freshdirect. Fresh Direct. (2022). Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://www.freshdirect.com/srch.jsp?searchParams=butter

(33) Nations, U. (2013, December 3). World must sustainably produce 70 percent more food by mid-century – UN report | UN news. United Nations. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2013/12/456912

(34) Hydroponics vs soil, all you wanted to know. Hydroponics vs soil, all you wanted to know – Science in Hydroponics. (n.d.). Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://scienceinhydroponics.com/2021/04/hydroponics-vs-soil-all-you-wanted-to-know.html?utm_source=rss&print=print

(35) Top four irrigation techniques. DripWorks. (2020, May 27). Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.dripworks.com/blog/top-four-irrigation-techniques