How Fast Fashion Pollutes the Planet and Exploits People

When you pick up a $10 t-shirt or scroll through a flash sale online, it is easy to forget the behind-the-scenes processes that each piece of clothing goes through before it reaches your hands. Each piece of clothing represents an intricate web of global production, from cotton fields and polyester factories to dyeing plants and sewing floors, spanning across multiple continents. Fast fashion, defined as the rapid production of inexpensive, trend-driven clothing, has completely transformed how the world shops. What was once a slow, seasonal cycle of fashion collections has evolved into a constant update of “new arrivals” designed to keep consumers buying week after week.

Yet, behind this illusion of affordability and convenience lies one of the most environmentally destructive and socially exploitative industries on Earth. The fast fashion machine operates on speed, volume, and disposability, which are three ingredients that have devastating consequences for both people and the planet. The growing demand causes factories to produce billions of garments each year, releasing massive amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Toxic dyes wind up in rivers, synthetic fibers release microplastics into oceans, and mountains of clothing pile up in landfills or are burned in open pits, polluting the air and soil.

At the same time, the industry’s relentless push for lower prices depends on the exploitation of vulnerable workers, mostly women in developing countries who live in unsafe factories for poverty-level wages. The rise of fast fashion over the past two decades has created an endless cycle of overconsumption, driven by marketing tactics that associate personal identity with constantly changing trends. Social media influencers, brand collaboration, and algorithm-driven advertising feed this consumer blow-up, normalizing a “buy, wear once, and discard” mindset. The affordability of these clothes masks their true cost: high carbon emissions, immense water use, toxic pollution, and the exploitation of millions of workers in developing nations worldwide. As consumers become more aware, the question isn’t just what we are wearing, but who and what pays the price for it.

The Carbon and Water Footprint of Your Clothes

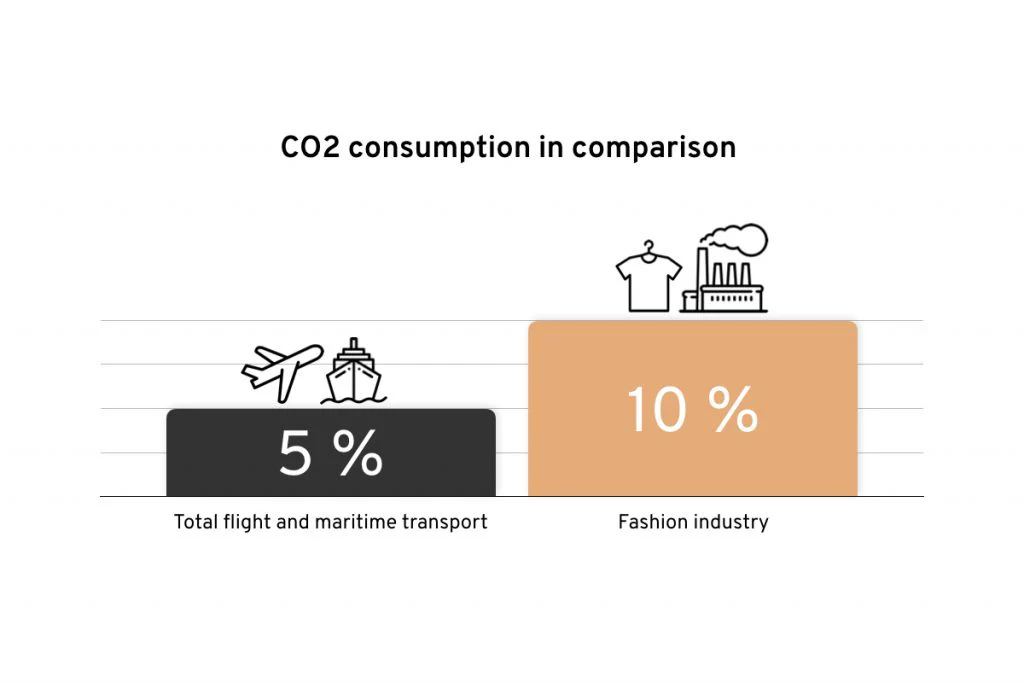

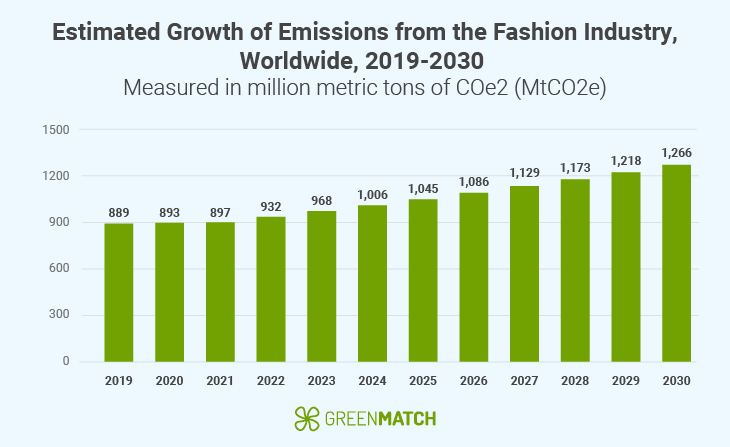

The environmental toll of fast fashion begins long before a shirt lands neatly folded on a store shelf or appears in an online shopping cart. Every garment has a long and complex life cycle that starts with raw material extraction and ends with disposal, often after being worn only a handful of times. The global fashion industry accounts for 8-10% of total greenhouse gas emissions, which is more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined (Maiti, 2025). This immense carbon footprint is a direct result of the industry’s dependence on energy-intensive production methods and fossil-fuel-based materials. Most of these emissions come from textile production and manufacturing, particularly from synthetic fibers like polyester, nylon, and acrylic, which are derived from fossil fuels and require significant energy to refine, melt, and spin into yarn (Benson, 2025).

Producing synthetic fabrics consumes vast amounts of nonrenewable energy, while natural fibers such as cotton also carry significant environmental costs. Cotton farming, often marketed as a “natural” alternative, is one of the most water-intensive crops in the world. It takes roughly 700 gallons of water to make a single cotton t-shirt and about 2,000 gallons to produce one pair of jeans (Maiti, 2025). In major cotton-producing regions like India, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan, this excessive water use contributes to the depletion of rivers and water sources. In contrast, heavy pesticide and fertilizer use make the soil and wildlife harmful. The environmental cost grows even higher when one considers the fossil fuels required for transporting these materials across continents for spinning, dyeing, and sewing before garments even reach consumers.

The dyeing and finishing stages of textile production are among the most destructive phases in the entire fashion supply chain. These processes use thousands of different chemicals, many of which are carcinogenic or otherwise toxic to aquatic life and humans. Factories frequently discharge untreated wastewater directly into rivers, canals, and groundwater sources, especially in regions with weak environmental regulations (Lam, 2025; Hydrotech, 2025). Across South and Southeast Asia, in places like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Indonesia, once-pristine waterways have become polluted with chemical runoff. These rivers often run bright blue, red, or green, depending on the week’s dye, transforming natural ecosystems into literal rivers of fashion waste. The contamination not only destroys aquatic habitats but also affects the communities that rely on these water sources for drinking, bathing, and agriculture.

Fast fashion also accounts for roughly 20% of global wastewater, a shocking statistic considering the growing scarcity of clean water in many garment-producing nations (Bailey, Basu, & Sharma, 2022). The cumulative effect of these industrial practices is insanely horrifying. Textile factories are now among the largest industrial polluters of freshwater systems worldwide, releasing effluents containing heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and chromium, as well as microplastics from synthetic fibers. These pollutants accumulate in soil and aquatic life, entering the food chain and threatening both biodiversity and public health (Bailey et al., 2022).

The more the fashion cycle grows and expands, the worse the environmental damage becomes. Each “drop” of a new collection fuels another round of production, which means more fossil fuels burned, more water extracted, more chemicals released, and more waste generated. The industry’s obsession with speed in its production comes at a harsh ecological cost, one that is mostly unseen by the average consumer. The next time someone adds a trendy top or discounted pair of jeans to their shopping cart, it’s worth remembering that behind each low price tag lies a trail of pollution that stretches from oil rigs to cotton fields to toxic rivers.

When discussions turn to the fashion industry’s environmental footprint, carbon dioxide emissions tend to dominate the conversation; however, a far more potent greenhouse gas often goes overlooked: methane. Methane is at least 28 times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere over 100 years than carbon dioxide, and its short-term warming potential makes it a critical target in the fight against climate change. Yet, despite its significance, methane’s connection to fashion, particularly through animal-based materials, remains largely hidden from public awareness (The Wall Street Journal, 2025).

Animal-derived textiles such as leather, wool, and cashmere represent only a small part of the industry by volume, about 3.8% of total apparel materials. Still, they are extremely responsible for methane emissions. These materials contribute to nearly 75% of the industry’s total methane output, generating roughly 8.3 million metric tons of methane annually, which is almost four times more than the total methane emissions of France (The Wall Street Journal, 2025). This extremely high statistic highlights an often-overlooked link between fashion and industrial livestock production, one of the most methane-intensive activities on the planet.

Leather production is a major culprit in this equation. The majority of leather comes from cattle, whose digestive processes release methane through fermentation. Each year, billions of cows are raised not just for meat and dairy but also for their hides, which the fashion industry transforms into handbags, shoes, belts, and jackets. The global demand for leather drives deforestation in places like the Amazon rainforest, where vast tracts of land are cleared to make room for cattle ranches. This deforestation not only destroys biodiversity but also releases the carbon stored in trees and soil, amplifying the overall greenhouse effect. The environmental cost of a leather handbag extends far beyond its stylish exterior, but it is linked to forest loss, methane emissions, and the degradation of vital ecosystems.

Similarly, the production of wool and cashmere contributes to the methane problem through livestock rearing, particularly sheep and goats. These animals emit significant amounts of methane as part of their digestive process, and their overgrazing can lead to severe land desertification, especially in regions where cashmere goats are raised in large numbers. As pastures are stripped bare, soil erosion increases, dust storms become more frequent, and local communities suffer from the loss of usable land.

Compounding the issue is the widespread perception that animal-based textiles are already “natural” and therefore more sustainable than synthetics. In reality, the environmental trade-offs are complex. While synthetics derive from fossil fuels, animal-based materials contribute to methane emissions, deforestation, and water contamination. The leather tanning process, for instance, uses chromium salts and other toxic chemicals that can seep into waterways, adding to pollution (Bick, Halsey, & Ekenga, 2018). In this way, the “naturalness” of animal fibers becomes a misleading form of eco-mythology, one that masks the full climate impact of these products.

How can we solve this?

The methane problem within the fashion industry requires both innovation and accountability. Brands cannot keep ignoring the effects of their material choices. Transitioning to plant-based leathers, lab-grown textiles, or bio-based fibers could significantly reduce methane emissions and land use. These alternatives, made from materials like pineapple leaves, cactus fibers, or mycelium (mushroom roots), offer a healthy and more environmentally friendly path forward. However, they remain in early stages of development. Although some forward-thinking fashion groups, like people experimenting with these materials, have already begun working with these options, which signals a shift toward more sustainable material sourcing.

Ultimately, the methane issue underscores a broader reality of fast fashion: the industry’s environmental footprint has numerous harmful effects. It cannot be addressed by focusing solely on carbon dioxide. True sustainability requires many other views that account for all greenhouse gases, including methane, as well as the social and ecological systems that sustain life on Earth. By acknowledging the hidden costs of animal-based textiles, consumers and companies alike can begin to make more informed, ethical, and climate-conscious choices.

The Water Crisis Behind the Scenes

Beyond carbon and methane emissions, the fashion industry’s impact on the planet runs deep, quite literally, through the contamination and depletion of one of Earth’s most essential resources: water. Every stage of garment production, from fiber collection to dyeing, finishing, and washing, consumes or pollutes water. The result is a global crisis unfolding behind the scenes that threatens both ecosystems and human health.

In many garment-producing regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, textile factories operate near rivers and lakes that have become dumping grounds for untreated wastewater. The dyeing and bleaching of fabrics, which are a part of critical steps in achieving vibrant colors and soft textures, often release a toxic mixture of chemicals into waterways. These chemicals and toxins include formaldehyde, heavy metals like lead and mercury, chromium compounds, and azo dyes, many of which are carcinogenic or harmful to aquatic organisms (Bailey, Basu, & Sharma, 2022). Without strict environmental regulations or proper wastewater treatment systems, these substances leach into rivers and groundwater, transforming once-clear water bodies into vivid, toxic streams (Lam, 2025; Hydrotech, 2025).

For example, in Bangladesh’s Dhaka district, home to thousands of textile and dyeing factories, rivers like the Buriganga and the Turag have turned black from pollution, and their surfaces are coated in chemical foam. Fishermen can no longer earn a living from the poisoned waters, and communities that depend on these rivers for drinking and washing face health consequences, including skin diseases, gastrointestinal illnesses, and reproductive disorders (Bailey et al., 2022). This pattern repeats across textile hubs in India, China, and Indonesia, where economic growth has often come at the expense of environmental degradation.

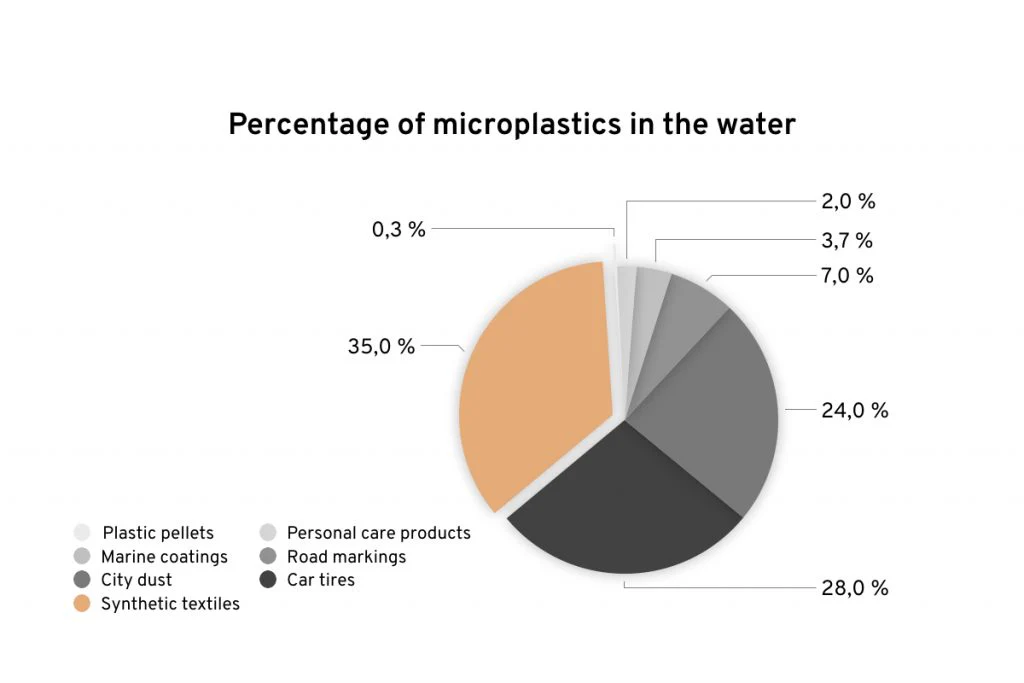

Even more subtle but just as harmful is the microplastic pollution released by synthetic fabrics like polyester, nylon, and acrylic. Each time these garments are washed, thousands of microscopic fibers are shed, escaping wastewater treatment systems and flowing into rivers, lakes, and eventually, the oceans (Hydrotech, 2025). Studies have shown that these microfibers now account for a significant portion of the microplastic pollution in marine environments. Once in the water, they are ingested by plankton, fish, and shellfish, meaning that the tiny threads from a cheap polyester dress can ultimately end up in the human food chain (PSCI, 2020). Scientists have even detected microplastics in human blood, lungs, and placental tissue, raising alarming questions about long-term health impacts.

Water consumption and wastewater

The scale of water consumption is just as troubling. Beyond the dyeing and washing stages, raw material production, particularly cotton farming, demands immense amounts of freshwater. Entire regions have suffered ecological damage due to water diversion for cotton irrigation. One of the most infamous examples is the Aral Sea disaster, where decades of cotton cultivation in Central Asia drained what was once the world’s fourth-largest lake, leaving behind a toxic, dust-filled wasteland. Such examples underscore the devastating, far-reaching consequences of the fashion industry’s thirst for water.

Globally, the fashion industry is responsible for around 20% of all industrial wastewater (Bailey et al., 2022), a scary statistic that underscores the industry’s dependence on clean water. Yet many of the countries most deeply affected by textile pollution already struggle with chronic water scarcity. In parts of India and China, residents must choose between using contaminated water or going without water. As the climate crisis intensifies and freshwater becomes increasingly scarce, the water demands of fast fashion appear not only unsustainable but also unjust.

What can we do and is it working?

Addressing this crisis requires both technological innovation and systemic reform. Some brands and factories have begun investing in closed-loop water systems that treat and reuse dye water, dramatically reducing discharge. New enzyme-based and plant-based dyes are also being developed as cleaner alternatives to synthetic chemicals. However, these solutions are still not used as widely as they could be, as many fast-fashion suppliers prioritize cost and speed over environmental responsibility.

These fibers now make up 35% of all primary microplastics in the world’s oceans (Princeton Student Climate Initiative, 2020). As fashion’s production has increased, so have microplastic concentrations in water bodies, contributing to the long-term contamination of food chains. Without major systemic reform, fashion’s water use and pollution could make clean water increasingly scarce in textile-producing regions, further stressing ecosystems and environments (Earth.Org, 2025).

The industry’s water footprint is not just an environmental concern; it is a crisis. For every pair of jeans sold, families elsewhere lose access to safe drinking water.

Waste, Overproduction, and the Illusion of Sustainability

In recent years, many brands have launched “eco” or “conscious” collections of clothes, often using words like recycled materials or ethical sourcing. Although these efforts are hidden within the contradiction of fast fashion. Sustainability cannot coexist with overproduction.

Despite marketing claims, the volume of global fiber production continues to soar, reaching 132 million tons in 2024, which is up from 125 million tons in the previous year (Benson, 2025). Synthetics now account for 69% of all textile materials, and although recycled polyester use has increased slightly, 88% of fibers remain fossil-based, meaning that overall emissions have actually risen by 20% over five years (Benson, 2025).

Meanwhile, waste piles in landfills are higher than ever. About 85% of all textiles end up in landfills or are incinerated each year (One Green Planet, 2025). Clothing that doesn’t sell is often burned or shredded to protect “brand value,” which is a company’s way to avoid resale at lower prices. Although even donations to thrift stores and charities are not immune. Most clothes are shipped to countries in the Global South, where they overwhelm local markets and contribute to pollution when discarded in new areas.

Many “sustainability” campaigns serve as greenwashing. Greenwashing is the idea that companies make it seem as though their clothes and their production are more sustainable than they actually are. Although fast fashion’s model depends on producing too much, too cheaply, and too quickly. No amount of recycled fabric can offset an industry that is built on disposability.

The Human Cost of Cheap Fashion

Behind every affordable outfit lies an invisible human story. Millions of garment workers, who are primarily women in countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India, labor long hours for poverty wages in unsafe conditions. The 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Dhaka, which killed over 1,100 workers, exposed the deadly consequences of the fast fashion supply chain (Wikipedia Contributors, n.d., 2025). In this tragedy, the entire Plaza collapsed onto workers, where five fashion factories were stationed. These conditions, even in the case of building failure, are one of many examples of how harsh working conditions in the fast fashion industry can truly be. And still, more than a decade later, many factories remain structurally unsafe, and workers still face intimidation, wage theft, and exposure to toxic chemicals (Bick, Halsey, & Ekenga, 2018).

Fast fashion is not only an environmental issue but also a matter of global environmental injustice. The same factories that pollute local air and water also exploit local labor. Waste from production is frequently dumped in the very communities where these workers live, forcing them to suffer from economic and ecological burdens. These conditions are similar to colonial patterns of resource extraction, in which wealthier nations externalize environmental and human costs onto the global community (Bick et al., 2018).

The burden extends beyond production. Informal waste pickers in African and South Asian countries handle mountains of discarded clothing exported from the Global North, often without protective gear. Burning synthetic waste releases toxic fumes, exposing entire neighborhoods to respiratory illnesses. The human toll of fast fashion is just as real and urgent as its environmental footprint.

The Greenwashing Trap

Corporate “sustainability” messaging to customers and consumers has become a new defining feature of modern fashion marketing. Phrases like “carbon neutral,” “eco-friendly,” and “made with recycled materials” are often plastered across websites and tags. Yet behind these words, few brands disclose verifiable data about their environmental performance (Gray, 2024).

Many companies exaggerate the benefits of small initiatives, such as switching to organic cotton or installing recycling bins in stores, while ignoring the larger systemic issue of overproduction (Earth.Org, 2025). A 2024 Earth Day report found that less than 20% of brands publishing sustainability statements provide transparent data about their supply chains or waste management practices (Gray, 2024).

Even when garments are made from recycled fibers, they often cannot be recycled again, because blended materials (like polyester and cotton mixes) are nearly impossible to separate. So, “recycled” clothing usually up in landfills after a short life span. Years before “greenwashing” became a well-known term, several people, including Claudio, warned others about this paradox, stating that “sustainability in fashion cannot be achieved without changing consumer behavior and production volume” (Claudio, 2007).

The attraction to “eco-friendly” labels is a shocking, overused fad that leads to overconsumption by customers and causes more negative, detrimental effects on the environment. Real change requires confronting fast fashion’s growth-driven business model, and not just barely tweaking its overall image.

Circular Solutions and the Future of Sustainable Fashion

Although the overall picture of fast fashion may seem dark, meaningful change is possible. Researchers, innovators, and policymakers are developing alternatives that could transform fashion’s footprint.

Circular fashion, a model in which materials are reused, repaired, or recycled into new garments, offers one of the most promising paths forward (Gray, 2024). Instead of the traditional linear model of “take, make, waste,” circular systems aim to close the loop by designing products for durability and recyclability. Some examples of circular fashion include clothing rentals, reselling and thrifting, repairing clothes, and upcycling, all of which extend the life of garments one may already own.

Governments and international agencies are beginning to act. The European Union’s Textiles Strategy calls for mandatory durability standards, repairability labeling, and producer responsibility for waste. In Asia, pilot programs are testing low-water dyeing technologies and wastewater recycling (Lam, 2025). Some places, including China, have been piloting waterless textile dyeing, while others, like India, have implemented improvements in their water-recycling facilities.

Consumers also play a crucial role. By choosing fewer, high-quality garments, supporting transparent brands, and repairing rather than replacing clothes, individuals can shift their dependence toward sustainability. The slow fashion movement, which advocates mindfulness, longevity, and ethics, is a growing movement against disposable culture.

Although systemic change must also come from a higher power. Governments need to enforce environmental regulations, invest in clean technologies, and innovativize circular manufacturing (the true production of recycled and more sustainable sourcing) (Gray, 2024; Claudio, 2007). Without policy intervention, voluntary corporate promises will continue to remain ineffective.

A Call for Conscious Consumption

Every stage of a garment’s life, from obtaining cotton to disposal by humans, leaves an environmental footprint. But raising awareness of the issue can be a true start toward transformation. As consumers, we truly hold the power through our choices.

To make a difference, we can:

- Buy less and buy better: choose durable, timeless pieces instead of short-lived trends

- Support transparency: favor brands that publish detailed sustainability reports and third-party audits

- Repair and reuse: extend the life of garments through repairing, swapping, and upcycling

- Resist greenwashing: look beyond marketing claims and verify environmental certifications

The fast-fashion crisis reflects a larger truth: unchecked consumption cannot coexist with the survival of our environment or planet. As Gray stated, “Fashion’s dirty little secret isn’t just pollution- it’s our willingness to ignore it” (Gray, 2024).

Fast fashion is not just a trend. It is a warning sign of how far industries can push ecological boundaries. But awareness does create accountability, and accountability drives change. The more we understand what we are harming, the closer we can come to transforming an industry that profits from our planet’s decline into one that respects both the people and the planet.

Bibliography

Al Jazeera. (2021, November 8). Chile’s desert dumping ground for fast fashion leftovers [Photograph]. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2021/11/8/chiles-desert-dumping-ground-for-fast-fashion-leftovers

Americas Quarterly. (n.d.). [Photograph]. (2025) Photograph of oil pollution in a river. https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/oil-sewage-heavy-metals-the-pollution-plaguing-latin-americas-water/

Arndt, B. (2023, October 19). Fast fashion failing fast? Environmental effects add up after swift cheap clothing has hit the racks. Crimson Newsmagazine. https://crimsonnewsmagazine.org/64042/will-run-front-banner/fast-fashion-failing-fast/

Bailey, K., Basu, A., & Sharma, S. (2022). The environmental impacts of fast fashion on water quality: A systematic review. Water, 14(7), 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14071073

Benson, S. (2025, September 18). Material production reaches record heights—And emissions grow. Vogue Business. https://www.voguebusiness.com/story/sustainability/material-production-reaches-record-heights-and-emissions-grow

Bick, R., Halsey, E., & Ekenga, C. C. (2018). The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environmental Health, 17(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0433-7

Brui, A. (2016, August). Is Fast Fashion Bad For The Environment? GreenMatch. https://www.greenmatch.co.uk/blog/2016/08/fast-fashion-the-second-largest-polluter-in-the-world

Circular economy fashion icons banner [Illustration]. (n.d.). Shutterstock. https://www.shutterstock.com/image-vector/circular-economy-fashion-banner-icons-editable-2242491555

Claudio, L. (2007). Waste couture: Environmental impact of the clothing industry. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115(9), A449–A454. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.115-a449

Earth.Org. (2025, January 20). Fast fashion: Its detrimental effect on the environment. https://earth.org/fast-fashions-detrimental-effect-on-the-environment/

Gray, A. (2024, May 29). Fashion’s dirty little secret. Earth Day. https://www.earthday.org/fashions-dirty-little-secret/

Greenpeace International. (2017). What are microfibers, and why are our clothes polluting the oceans? [Infographic / chart]. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/6956/what-are-microfibers-and-why-are-our-clothes-polluting-the-oceans/

GreenMatch. (n.d.). The environmental impact of the fast fashion industry [Infographic]. GreenMatch. https://www.greenmatch.co.uk

Gooch, F. (2021, July 30). Garment workers at a factory in Bangladesh during the pandemic [Photograph]. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2021/jul/30/act-now-to-stop-garment-workers-being-abused

Hydrotech. (2025, October 15). The ugly truth: How fast fashion pollutes our drinking water. https://www.hydrotech-group.com/blog/the-ugly-truth-how-fast-fashion-pollutes-our-drinking-water

Lam, J. (2025, March 7). The devastating effects of fast fashion on water pollution. Seaside Sustainability. https://www.seasidesustainability.org/post/microbial-bioremediation-techniques-for-oil-spills-addressing-oil-contamination-1-1-3

Maiti, R. (2025, January 20). Fast fashion: Its detrimental effect on the environment. Earth.Org. https://earth.org/fast-fashions-detrimental-effect-on-the-environment/

One Green Planet. (2025). How the fast fashion industry destroys the environment. https://www.onegreenplanet.org/environment/how-the-fast-fashion-industry-destroys-the-environment

Princeton Student Climate Initiative (PSCI). (2020, July 20). The impact of fast fashion on the environment. https://psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/7/20/the-impact-of-fast-fashion-on-the-environment

The Wall Street Journal. (2025). Methane emissions remain a blind spot for fashion industry, report finds. https://www.wsj.com/articles/methane-emissions-remain-a-blind-spot-for-fashion-industry-report-finds-e6dca6d3

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Rana Plaza collapse. In Wikipedia. Retrieved November 14, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rana_Plaza_collapse

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Side view of the collapsed Rana Plaza building [Photograph]. In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rana_Plaza_collapse

World Resources Institute. (2017). The apparel industry’s environmental impact in 6 graphics [Infographic]. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/insights/apparel-industrys-environmental-impact-6-graphics