Understanding the Mechanics of Microplastics

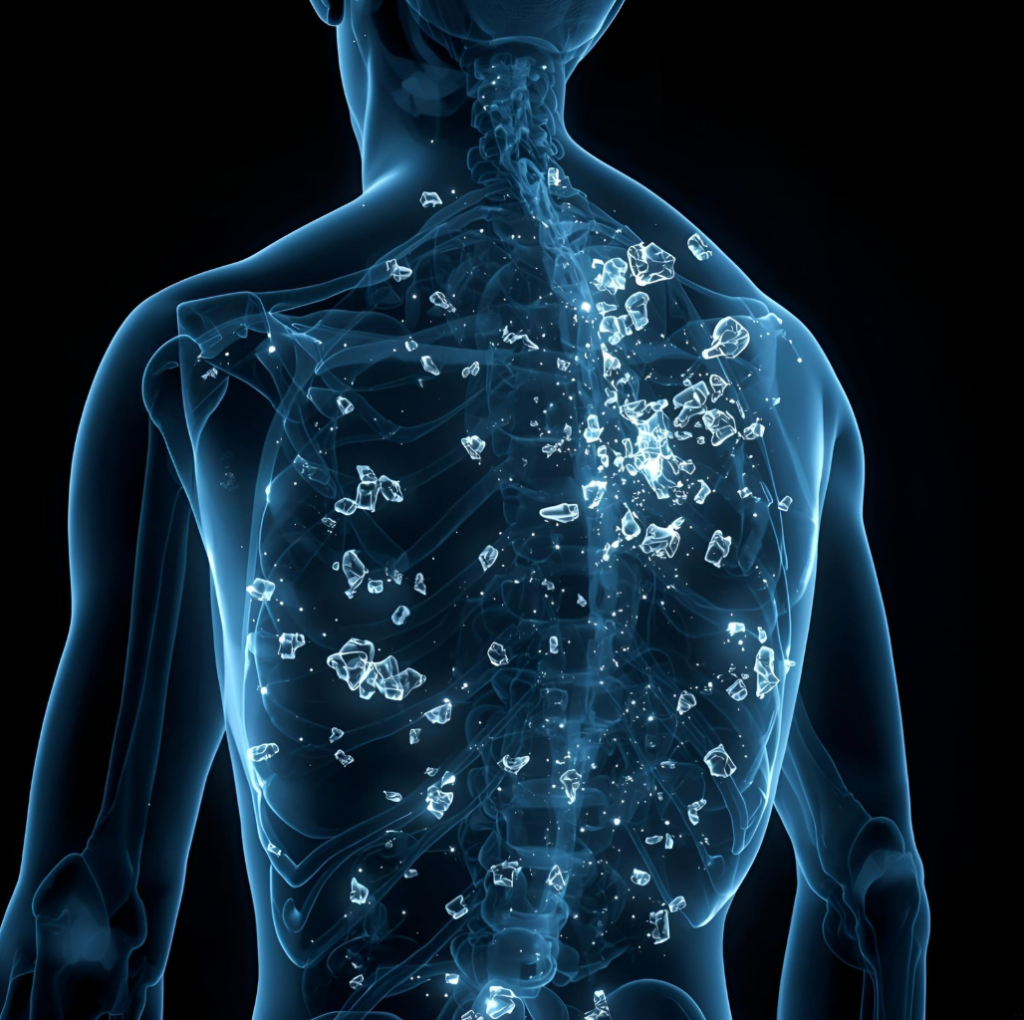

If you’re ever analyzing where the plastic you get rid of goes, you will find that it may never completely depart from you. Instead, you will come to realize your coexistence with microplastics–tiny, unseeable specks that pose detrimental harm to both human, wildlife, and environmental health. In fact, most Americans have enough microplastics in their brain to construct a plastic spoon. Urgently, we cannot dismiss the action we need to take to prevent these invisible invaders’ worsening consequences. The leftover plastic from production is often common in our society, with “The total plastic waste landfilled in USA remains relatively high, with 30.47 Mt (76%) landfilled, 12% incinerated, 4% mismanaged and only 5% recycled” (Houssini, Li, et al., 2025). With the majority of plastic placed into landfills, it is clear how much of the nation is dismantled and affected by this disaster. Grasping how microplastics are consumed, their dangers, and what we can do about this concern as a society is vital in comprehending the framework of this affair. Some may suggest that plastics are convenient, durable, and cost-effective. While that may offer some truth, these positions fail to recognize that the harms coinciding with microplastics are irreversible and not worth the slim benefits presented. The illusion of plastic positivity masks the reality of how degrading our overall health has become as a result of this problem. Although the current ramifications from microplastics cannot be reversed, the rise of awareness regarding this issue encourages consumers to educate themselves on these dangers, use plastics more responsibly, and implement a safer lifestyle. Without collective responsibility, ranging from individuals to governments and large corporations, the severity of this concern increases as time goes on. I share my passion regarding this discussion because far more damage than I could have imagined has been done, and it is critical to prioritize this knowledge in order to maximize our overall well-being. When consumers choose to incorporate their education on this topic alongside their own personal accountability and responsibility, society takes a step closer to living a more sustainable lifestyle by attempting to eliminate the dangers of microplastics. The above illustrations indicate how the human body can be invaded by microplastics. Captivating yourself in education surrounding the unseen intake of microplastics helps consumers recognize the effects that trickle into health and environmental risks and the need for a shift to sustainable living in our society, ultimately leaving us to fully considering what we can do in the future to gain flourishment and reach a state of overall peak performance.

(Chat GPT, 2025).

The Unseen Intake and Consumption

Do you really know what you’re consuming? It is a common misconception that in order to consume microplastics, you must have to directly eat a piece of plastic. This idea cannot be further from the truth; microplastics are so prevalent in our consumerism on a multitude of playing fields. While it is true that they can be found in food that utilizes plastic coverings, utensils, or packaging, they are commonly consumed elsewhere from the necessary items integrated in our everyday life. Most notably, “We encounter microplastics everywhere: from trash, dust, fabrics, cosmetics, cleaning products, rain, seafood, produce, table salt, and more” (Dutchen, 2023). Presenting the notion that they are only consumed through food consumption is weak and fails to project the entire landscape that surrounds this danger. Microplastics are unavoidable in modern life; no one is exempt from them and their consequences. The goal of this article is to inform consumers about the high dangers associated with microplastics, alongside how to limit their consumption of them. A key concept to recognize in this analysis is that their consumption is not solely through eating. For instance, consumers do not eat fabrics or cosmetics; however, microplastics trickle into the human system as “Researchers estimate that people inhale or ingest between 74,000 and 121,000 microplastic particles annually through breathing, eating, and drinking” (Dykstra, 2024). With so many pathways of microplastic consumption, it is important to pay attention to what we surround ourselves with. The graphic below visually illustrates a few examples in which microplastic intake can occur.

(Li, et. al, 2023).

Limiting the chances of consumption can be done through simple lifestyle changes, such as changing to cotton clothing, reducing the use of plastic products, and educating ourselves about the areas that may present harm. Action is demanded if we want to see a change because recognizing the dangers and actually putting safety measures into place are very different and offer independent responses. Microplastics engage with consumerism in a variety of mannerisms, and it is critical to recognize each in order to conceptualize this danger and turn to a more responsible living style. Alongside oral intake, inhalation, and skin contact that were previously mentioned, a graphic that represents the high transmission of microplastics from touching plastic products is listed.

(Chat GPT, 2025).

Not only are microplastics harmful to humans, but they are also often found in the organs of wildlife. As it is natural for humans to seek dominance over other living organisms, this should not override our ability to reflect our moral and caring background on different forms of life. Therefore, it is necessary to research how microplastics have invaded living systems as a whole. Taking into consideration that, “studies show that microplastics make fish and birds more vulnerable to infections” (LaBeaud, et. al, 2025), we can see how expansive and invasive this issue is to all forms of life. Understanding the dangers posed to other forms of life emphasizes how everyday habits connect to ecological damage through unintended consequences. This can be a result of how industrialized our world is becoming, and how our focus over time has shifted to production processes that are only beneficial to human evolution. The dangers fall beyond humans; they trickle into our wildlife and environment.

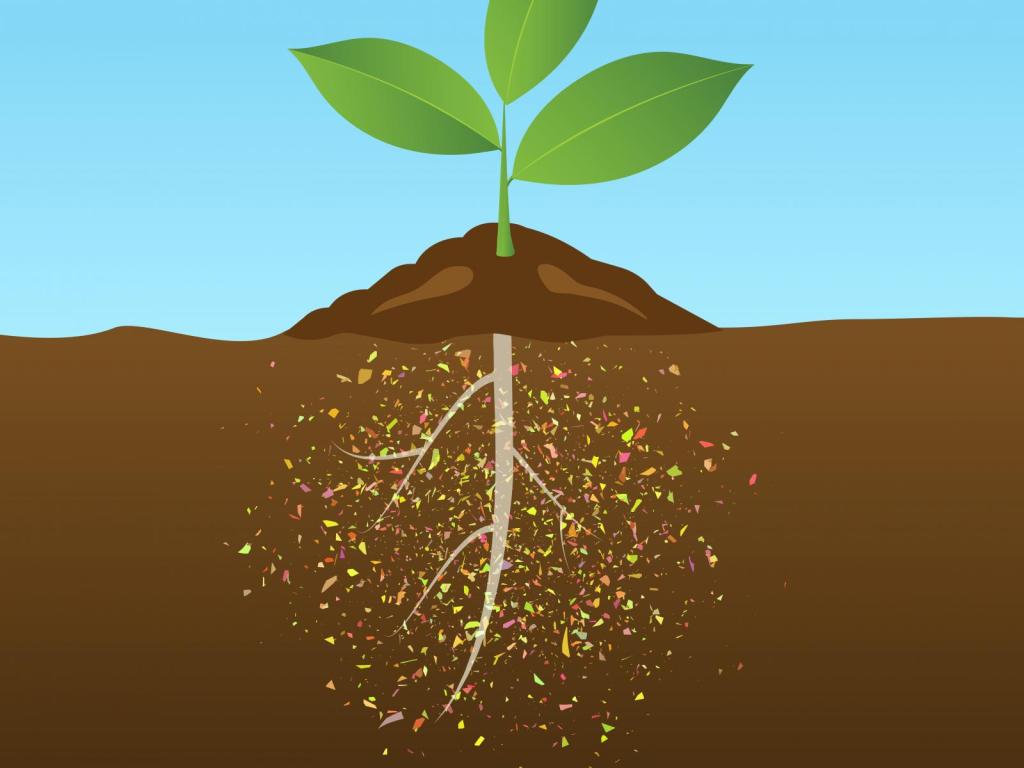

Our environment maintains the balance necessary for life on Earth. Research suggests that we need to live carefully beyond our food consumption and plastic prevalence, and go as far as recognizing the processes that take place where some of our nutrients are grown. If our food and crops are grown in toxic surroundings, what we put into our bodies becomes unsafe. These dangers are illustrated as a key aspect of agricultural production. It was found that “In Japan, evidence shows that microplastics, specifically from coated fertilizers, accumulate in agricultural soil, including paddy fields” (Carlini, 2022). With microplastics embedded in the fields that grow our crops, it is critical to research our products before consuming and or encountering any agriculture that may have been affected by these toxic chemicals. We can see how microplastics are rooted within the soil, similar to their systematic root in our society, below.

(Taylor, 2020).

An example of this scenario may reflect genetically modified products where plastic may directly come in contact with the soil in order to change the crop. Although microplastics play a role in the agricultural production of our food, measures can certainly be taken to secure a more sustainable side of eating and living.

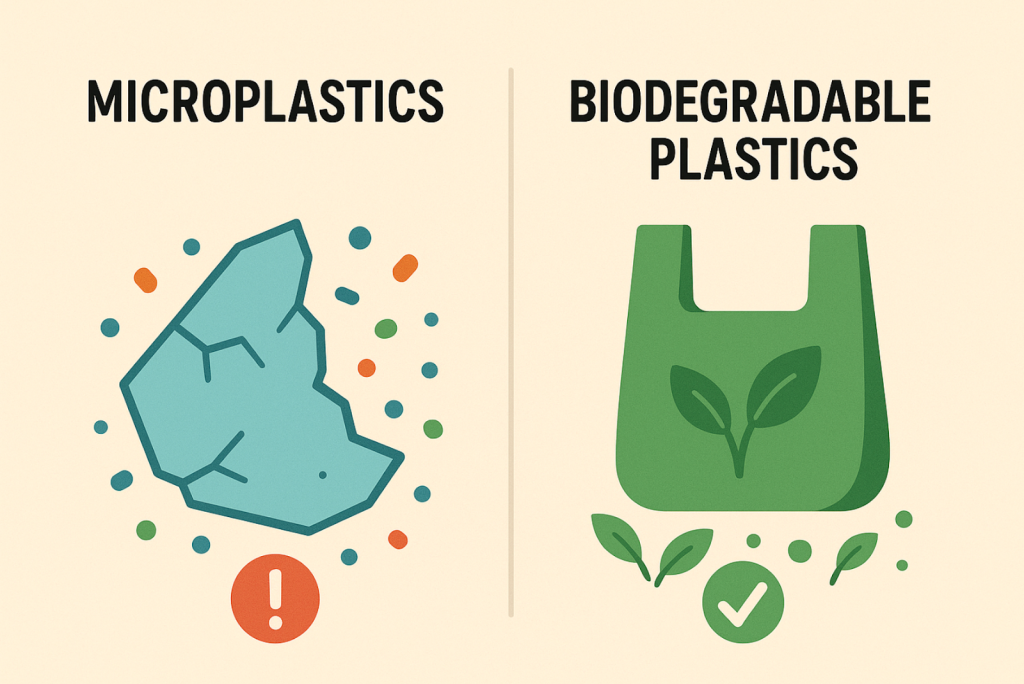

Some critics in favor of plastic usage may argue that plastics are convenient, therefore making microplastics unavoidable and a product we should precede normally in adapting to. While it is true that plastics are integrated into the majority of our lives, we can shift to a safer version of their existence. This can be done through the proposal of more innovations and alternatives, such as biodegradable plastics. As a result, “most biodegradable polymers decompose into environmentally acceptable products, such as water, carbon dioxide, and biomass,” (Malafeev, et. al, 2023). In order to keep up the production and health of humans, repositioning our plastic production is critical. Unlike conventional plastics, biodegradable plastics eliminate the likelihood of microplastics that would persist in our environment for decades and even centuries. In this way, the decomposition of plastics is extended as an opportunity to retrieve the purity of our sustainability. We can appreciate this innovative pivot because “A 2024 meta-study confirmed that biodegradable microplastics continue to break down in soil environments primarily through hydrosis, preventing accumulation of persistent microplastic fragments” (Brunn, 2025). Confirming the prevention of microplastics through new plastic innovation is a key factor to the start of recognizing how vital and easy it is to eliminate sources that destroy our bodies and environment. Using biodegradable plastics is one step closer to ending the cycle of pollution. Below is a graphic that articulates how biodegradable plastics conform to a greener sense of living.

(Chat GPT, 2025).

In the end, these efforts demonstrate less waste production and microplastic consumption, which is holistically better for the environment and human sustainability. Continuing, biodegradable plastics are in a position to be more accessible to the public because “Traditionally, biodegradable plastics have relied on sources like cornstarch and sugarcane. However, new materials such as algae, mushroom mycelium, and agricultural waste are emerging as promising alternatives” (Lake, 2024). The use of friendly sources contributes to clean consumption products and processes. Clean products may then reduce reliance on harmful fuels, promote the economy through agricultural production, and encourage green industries. Switching from plastics to biodegradable plastics can place us in situations that are of the public’s best interest, in terms of biological, ecological, and economic health. The description of how microplastics make their way into the food chain places emphasis on how important this issue is and offers us insight into how the construction of packaging and materials matters.

The Health and Environmental Risk

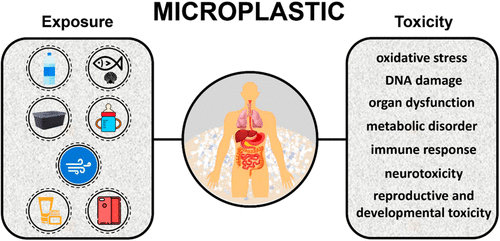

The next contribution of microplastics following their consumption illustrates their hazardous demeanor. Microplastics leave long-lasting, and even possibly fatal, effects on humans, wildlife, and the environment. With instability and uncertainty in the threats that follow the prevalence of these invisible invaders, there is no option except to recognize and find solutions to the persisting harm. First and foremost, “Microplastics are not only toxic itself but also carriers for many pollutants to enter biological tissues and organs,” (Li, et. al, 2023). As we realize how our health systems can be affected, we can understand where the foundation of these prolonged dangers stems from. It is evident that they impose a dual threat and are the host for other harmful substances. We can see how the exposure from this item trickles into our bodies which are then submerged in toxicity.

(Li, et. al, 2023).

Acknowledging the origin of these hazards can help us combat the resulting harmful response. To continue, microplastics have been identified in various parts of our anatomy, increasing the areas that are challenged. Specifically, “Microplastics have now been detected throughout the human body–including the blood, lungs, and liver and even lower limb joints”, alongside “evidence of microplastics in our brains” (Myers, 2025). These areas of the human body that can be consumed by these particles explain how the outcome is far dangerous and can leave detrimental side effects that harm longevity and health. In addition, these organs are of priority to our function, which present an alarming effect and threat to how our body can work to the best of its abilities. Research is still growing, but so far, “studies indicate that they can increase the likelihood of heart attack, stroke, and even Alzheimer’s” (Meyers, 2025), together with, “A review of some 3,000 studies implicates these particles in a variety of serious health problems. These include male and female infertility, colon cancer and poor lung function” (Colliver, 2024). Microplastics are persistent, pervasive, and prominent in our bodily functions. With their commonality expanding more rapidly, the younger generations are seeking exposure to these toxins at earlier stages in their life. Consequently, they are put at a higher risk for these chronic illnesses and are prone to experience health problems earlier in their life than the average middle-aged American does today. This statistic can only be projected to increase unless action is taken promptly. The image below reiterates how bold, capitalizing, and damaging this problem is. The large words and bold text should stand out, relaying an important message.

(Chat GPT, 2025).

The infiltration of these particles into the human body is life-threatening, hence why society needs to minimize their consumption. If we do not take action on this matter, we are practically asking for disorders that correlate with decreased longevity. This evidence imposes proof of irreversible damage, hence reflecting the importance of urgency in this topic.

Additionally, wildlife ecosystems are susceptible to similar health concerns promoted by these particles. Both aquatic and terrestrial environments are invaded. Not only are the habitats susceptible to microplastic harm, but the physical animals also face repercussions as a result of human ignorance. Through expansive examinations, “In 2023, Wageningen University collected and evaluated the dead bodies of 26 Northern Fulmars and found that 88% had plastic in their stomachs, with an average of 24.5 pieces of microplastics per bird” (Leviker, et. al, 2024). With this study conducted in 2023, we can only imagine that the increasing number of these microplastics will expand in the coming years, assuming no further action is put into place. This study stresses the severity as it indicates specific numbers that are present in the birds. Furthermore, we can see visuals that replicate what the inside of an animal may look like as a result of this complication.

(Canva 3D, 2025).

(Leviker, 2024).

We can analyze that this level of ingestion can lead to internal injuries, poisoning, and death. As plastic takes up the stomach space of these animals and releases harmful chemicals, there is an indication that entire food chains and functions can be disrupted. Honoring the fact that the harm beyond the consumption of microplastics doesn’t end at humans, but rather threatens entire ecosystems and our biodiversity, truly puts into perspective how massive and invasive these specks are, offering a powerful warning. By the same token, microplastics don’t halt with living systems but continue to prevail throughout our geographies.

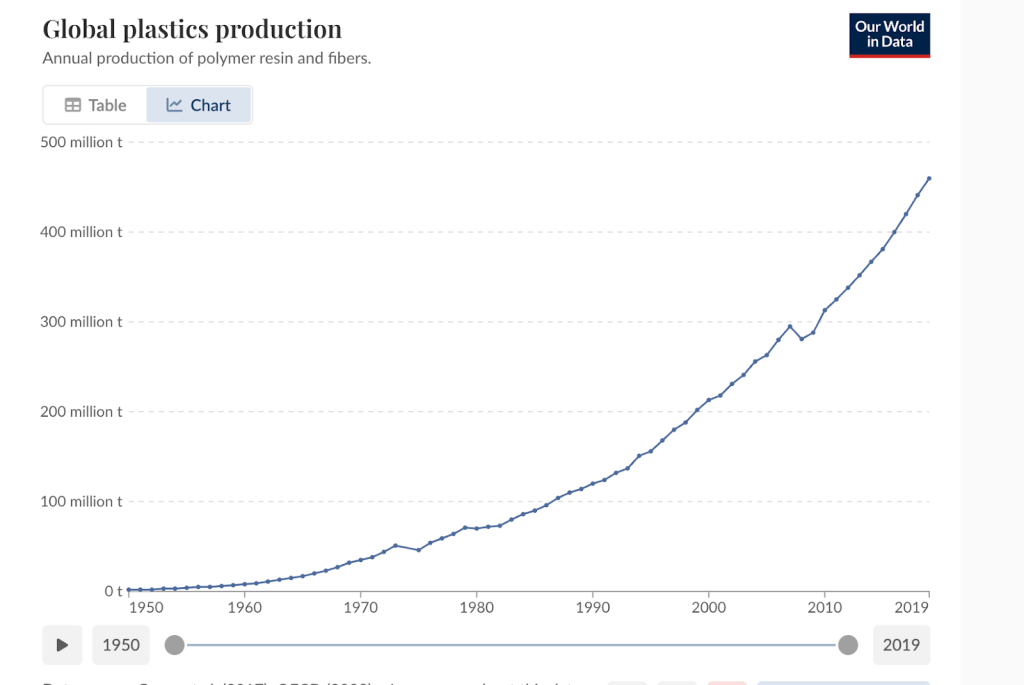

Microplastics offer tremendous harm to our environment and physical surroundings. Whether this be apparent through water and soil pollution, waste production, or landfills, to name a few, microplastics release their toxins into our living space. The pollution and toxins in nature are often derived from the way, “Microplastics are introduced to the environment through atmospheric deposition, land-based sources, fertilizers, artificial turf, road, landfill and air transportation, textiles, tourism activities, marine vessels, and aquaculture” (Lamichhane, et. al, 2022). The ramifications that serve as an integral part of environmental harm need to be combatted to reconstruct our unhealthy living to a healthier agenda. This quote draws on the concept that even remotely clean environments are vulnerable to contamination, showcasing how important it is to recognize what we are consuming and how to protect our consumption intake. Our human health starts with our environmental health, and that is a critical standpoint to realize if any change is ever going to be made. The goal of this text is to expand consumers’ thinking of microplastics, highlighting the areas that are exposed to threats. The protection of the environment and people go hand in hand, emphasizing the importance of monitoring your surroundings. Our environmental health is loaded with harm, as “Since 1950, approximately 8.3 billion tons of plastic have been produced, with an estimated 6.3 billion tons disposed of waste” (Kitajima, 2023). We can see that plastic accumulation is not only indicated as a modern problem, but also a product of environmental neglect and human incomprehension. The following figure depicts the rise in global plastic production between 1950-2019, which directly correlates to the increase in pollution on our globe as seen in recent decades.

(Samantaroy, 2024).

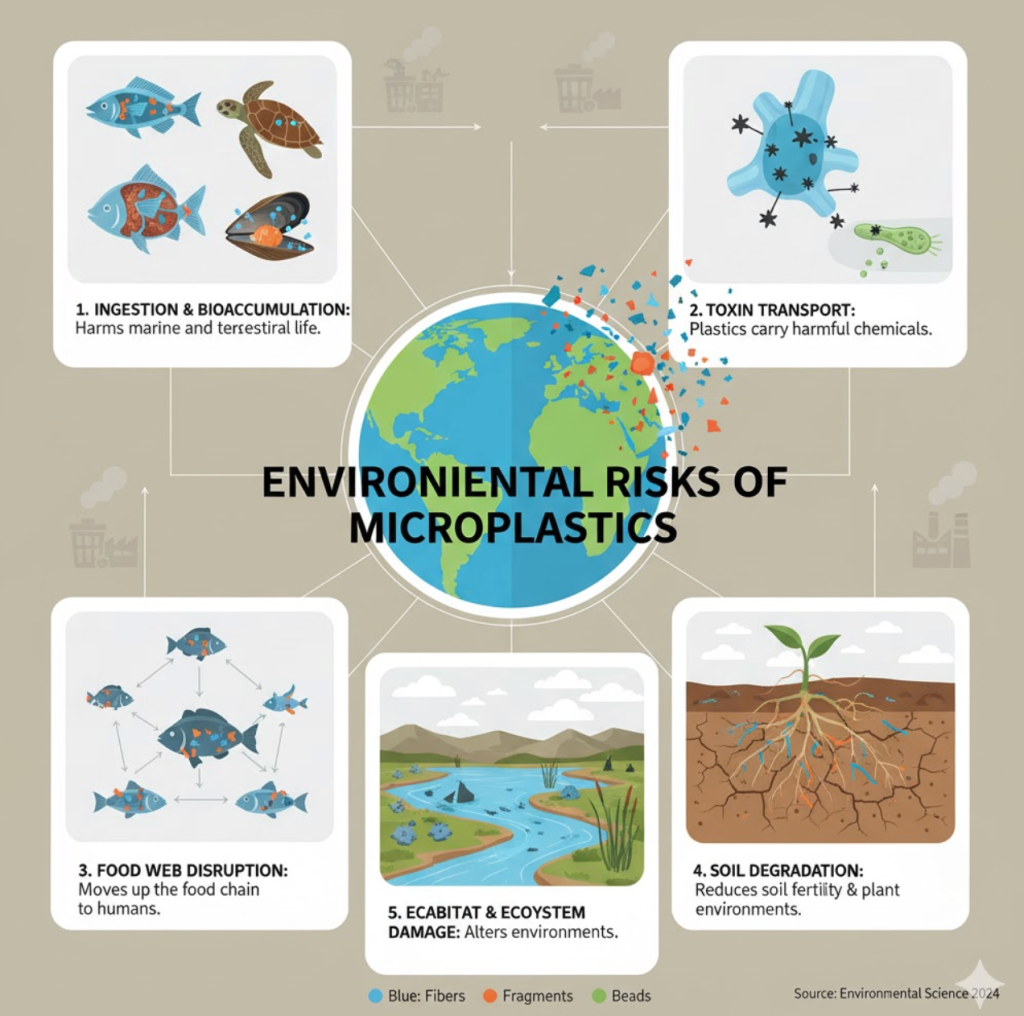

With the ability to see the cause and effect of plastic and microplastic production through quantitative evidence, the magnitude of the problem is argued. Moreover, the next graphic illustrates the various ways in which microplastics may present harmful effects to the environment. As you can visualize these effects, it is hoped that a more educated and informed audience will be able to take action in lessening these risks.

(Gemini, 2025).

On one hand, producers contend the durability of plastic to be top-tier, heightening its materialistic value in examples such as packaging, bags, water bottles, etc. However, in reality, this stance actually undermines the durability and presents a false sense of benefit for the usage. The material may be durable for the moment, but the response of the use presents a larger concern. The one-time use of a plastic product is not comparable to the harm it is embedded with. Specifically, products such as straws, wrappers, and water bottles present a singular usage combined with a multitude of lasting effects. Recognizing that “Approximately 8 million tons of plastic enter our oceans annually, much of which is Single-use, disrupting ecological balance” (Yerramsetti, 2025), can show concerns regarding how far a single piece of plastic product can travel. So much so that our aquatic living systems are highly contaminated.

(Readfern, 2020).

Understanding the imbalances when weighing out the pros and cons of plastic durability is significant in creating sustainability. Especially from this previous quote, we can understand how inconsistent and contradictory the stance supporting plastic durability can be. The study of how microplastics have an effect on humans, animals, and the environment is vital in understanding how harmful the consumption of microplastics truly is. Instead of letting these issues persist, we can turn to plastic alternatives and clean up after ourselves through recycling. The image below is a visual representation of what our current oceans may look like: animals circulating waters that are flooded with plastic.

(Gemini, 2025).

The Sustainable Pivot Society Needs

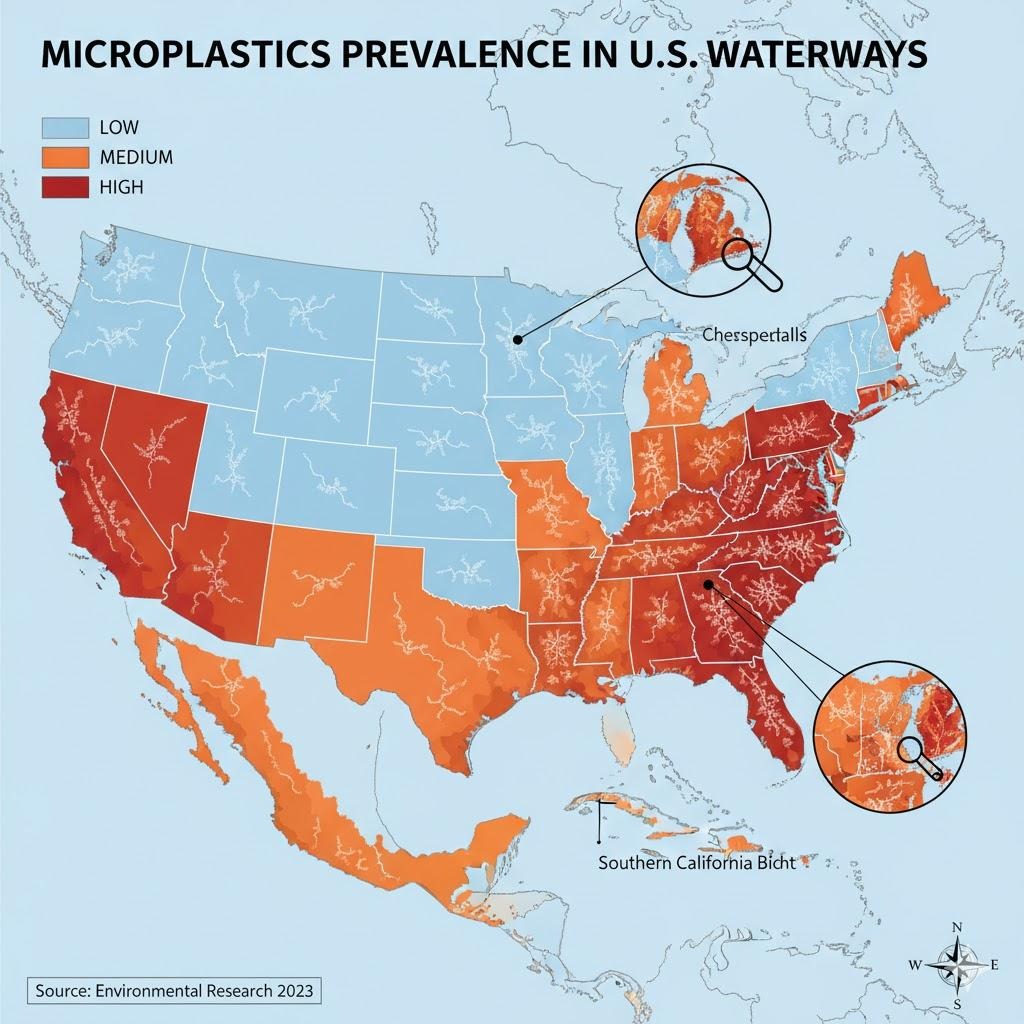

Microplastic consumption is a global issue. There are no constraints on who it can affect; no one is invincible to these invaders. As a society, we can only reduce the consumption and prevalence of these particles with full efforts at hand. This matter has become a shared responsibility that forces our generation to act together. Contributing to a healthier future begins with knowledge and ambition. Nevertheless, it is becoming more and more common to acknowledge the impact of microplastics, especially for those of younger generations. Many educational institutions, for example, The Pennsylvania State University, have begun to incorporate anti-microplastic living suggestions into sources accessible to their students and the public. In an article written by Penn State titled, “Microplastics: Sources, health risks, and how to protect yourself”, the university suggests that to minimize microplastic consumption, humans should see that, “First, you can opt for reusable products over single-use plastics”, and, “Second, choose natural fibers over synthetic” (Nyoni, 2025). These simple, yet powerful actions can fall under the category of efforts that change consumer habits for the better. Especially by choosing natural fibers, such as linen and wool, the hidden efforts of plastic pollution can be minimized. This showcases how decisions at the individual level relate to modern consumerism. These clothing styles, for example, are one way in which higher powers, such as clothing brands and stores, can contend for an impact in the consumer market through the regeneration of friendly materials. On a more generic level, “Public education, research, and collaboration are key to reducing microplastics and ensuring effective, transparent solutions” (Nyoni, 2025). This quote draws on the idea of collective responsibility and strategic approaches that can be taken by mainstream industries to generate knowledge for the public. Specifically in the U.S., we can see the indication of microplastic prevalence in U.S. waterways, with the darker colors representing a high pollution rate for that state.

(Gemini, 2025).

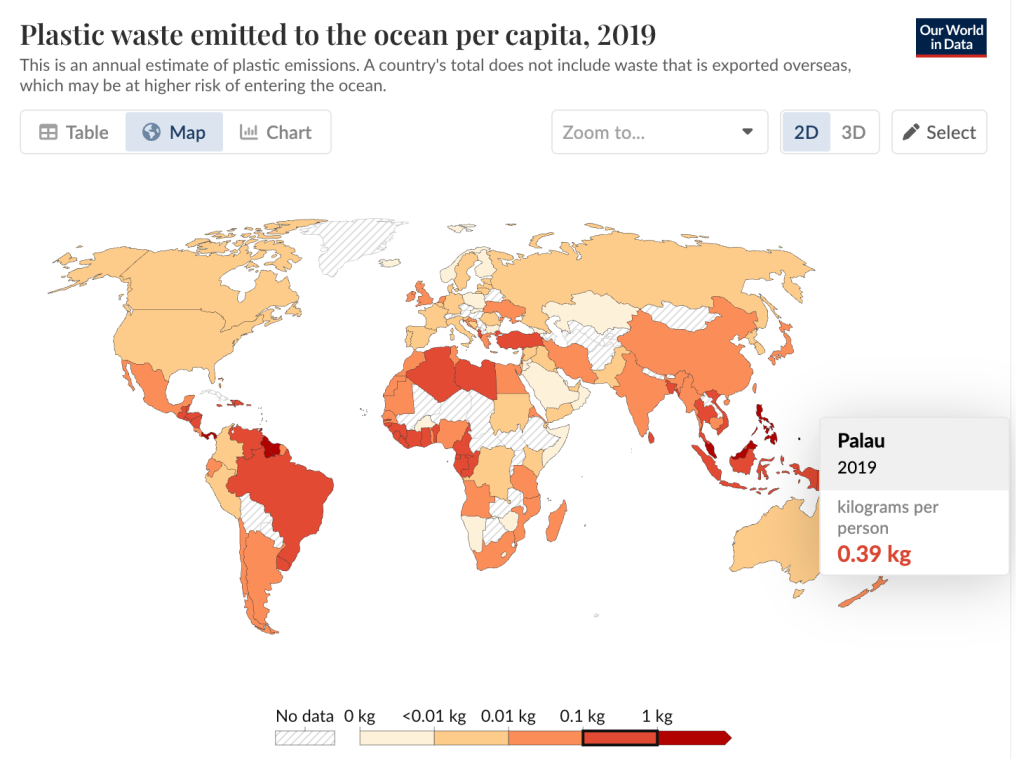

With U.S. institutions such as Penn State taking control over this issue by informing the public, it is hoped that this graphic will convey lighter colors in the coming decades. It is often overlooked how much of an influence huge industries can have on people. Hence, if these establishments can pivot their creations to play a part in healthy consumer living rather than company wealth or growth, global pollution would be a step closer to being abolished. With an account of, “The research shows microplastic consumption has risen sixfold globally since 1990, with Asian, African, and American countries all experiencing increases” (Samantaroy, 2024), we need to consider the changes that can be made in order to protect environmental and human longevity. The realm of this issue is far beyond where it should be, and efforts as collective citizens are needed to bring it back. The map highlights how much plastic waste in just 2019 was emitted to the ocean, throughout various parts of the world, with darker colors representing a higher emission rate.

(Samantaroy, 2024).

The ability to maximize the realms in which we focus our attention ultimately expands the relevance of the issue. The goal of this evidence is to provide insight into how big this issue is by showing how many populations it affects, as well as how it has increased over the years.

Some may suggest that while in the transition to more sustainable living, plastic does not need to be cut out due to the cost-effectiveness. This view goes as far as recognizing the low prices as a component that should overrule the harms presented by this product. However, this fails to reflect the true long-term costs that microplastics present to society. For one, factoring in the production, waste management, and climate damage that comes from plastic use adds additional costs that end up countering the “cheapness” of the material. For instance, “A new report by Dalberg commissioned by WWF reveals that the lifetime cost to society, the environment and the economy of plastic produced in 2019 alone was US$3.7 trillion – more than the GDP of India – and unless action is taken, this cost is set to double for the plastic produced in 2040” (Dewit, et. al, 2021). Microplastics present far worse long-term consequences that put healthy living at risk when in comparison to the short-term “cheaper” cost. Below we can see an illustration of the lifetime cost to society.

(Gillespie, 2020).

This contradictory ideology is a very influential reason for why this issue is misunderstood, ultimately leading to bad living styles for many individuals. Transitioning from an arrogant, uneducated society that consumes far more microplastics than imaginable, to citizens who grasp the importance of environmental and personal health standards, leaves a benefit for all aspects of society.

Considering the Future of Microplastics

Microplastics cannot be seen by the human eye, yet they are so invasive and prominent in society. As previously mentioned, they can be consumed through food, air, inhalation, and the everyday materials you surround yourself near. The dangers they present are deadly, ranging from impacts on human and animal bodies to environmental pollution. Unquestionably, society needs to begin taking measures to counteract this devastation. Billions of tons of plastic waste circulate the planet each year, promoting and growing the particles that diminish our well-being. Microplastics have become concerning as they are not only a main cause of pollution, but they are also a product of our regular lifestyle. Ignorance towards this matter allows microplastics to further accumulate and embed themselves, destroying the systems that promote sustainable living. With that, the longer society delays action, the more irreversible the consequences can become, and the harder it will be to combat these problems. The small size of these particles do not match the enormity of their problem.

(Murphy, 2025)

The evidence of microplastics found in wildlife and in bodily organs, including those of great importance such as the brain, lungs, and bloodstream, specifically articulates how relevant this problem is to every single individual. Public health is an essential priority that is of high importance. If measures are not taken to uphold standards in these significant areas, our improper action will leave future generations with a normalized lifestyle laced with microplastic particles. Taking effective measures can begin with education, and trickle into the sub-categories of using alternatives or bans, recognizing the flaws of plastic material, and acknowledging the unnecessary pollution expenses it promotes. Inspiring individuals to take control over their decisions creates investments that can hinder a new standard of sustainability. In addition, power structures, for example, the government and large corporations, can opt into eco-friendly processes that can exert influence on society. They can also enact regulations and bans that invest in safer manufacturing and production methods. This can include funding for biodegradable alternatives, sustainable packaging, and green technology. When these large powers lead by example, they set the cycle for consumers to follow. In this case, a new flow of responsibility and sustainability can be introduced in contrast with our current cycle of destruction. It is important to note that plastic and microplastics go hand in hand; what may be beneficial for a minute can be detrimental for a lifetime. The battle of this matter may begin with raising awareness about it, but it continues with transformation. We can utilize solutions that present less plastic usage and alternative materials such as biodegradable plastics. The way we live, consume, and value our surroundings is transformed through the accountability, innovation, and persistence our generation chooses to construct. Reducing microplastic consumption is not just a matter of convenience but rather an important issue of survival.

References

Brunn, M. (2025, October 14). Biodegradable plastics offer solution to microplastic pollution. RECYCLING magazine. https://www.recycling-magazine.com/2025/10/14/biodegradable-plastics-offer-solution-to-microplastic-pollution/#:~:text=A%202024%20meta%2Dstudy%20confirmed,.uk/resource%2Dhub.

Carlini, G. for I. E. L. (CIEL). (2022). Sowing a Plastic Planet: How Microplastics in Agrochemicals Are Affecting Our Soils, Our Food, and Our Future. Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL).

Chatgpt. (2025, November 14).

Colliver, V. (2025, September 17). Microplastics in the air may be leading to lung and colon cancers. Microplastics in the Air May Be Leading to Lung and Colon Cancers | UC San Francisco. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2024/12/429161/microplastics-air-may-be-leading-lung-and-colon-cancers

Dutchen, S. (2025, June 13). Microplastics everywhere. Harvard Medicine Magazine. https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/microplastics-everywhere?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Dykstra, P. (2024, June 20). Breathing in microplastics poses a growing health risk. EHN. https://www.ehn.org/breathing-in-microplastics-poses-a-growing-health-risk#:~:text=Scientists%20have%20found%20microplastics%20almost,microplastics%20to%20various%20chronic%20conditions.

Free AI 3D model generator | CANVA. (2025, November 14). https://www.canva.com/ai-3d-model-generator/

Google. (2025, November 14). Google Gemini. Google. https://gemini.google.com/app?is_sa=1&android-min-version=301356232&ios-min-version=322.0&campaign_id=bkws&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=2024enUS_gemfeb&pt=9008&mt=8&ct=p-growth-sem-bkws&gclsrc=aw.ds&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=20108148196&gbraid=0AAAAApk5BhlydaxjSlRmXBw6NiaHCy2RV&gclid=CjwKCAiAw9vIBhBBEiwAraSATp5lRhNkUpQRyOrFINz1-aAj3adjTu3qEBn0NAEOi6NRGMRmQFUF3xoCsA0QAvD_BwE

Houssini, K., Li, J., & Tan, Q. (2025, April 10). Complexities of the global plastics supply chain revealed in a trade-linked material flow analysis. Nature News. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-025-02169-5

Kitajima, Y. (2023, September). Is Biodegradable Plastic Good for the Environment? Exploring its Advantage and Disadvantage. Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. https://www.global.dnp/biz/column/detail/20173971_4117.html

LaBeaud, D., & Meister, K. (2025, January 29). Microplastics and our health: What the Science says. News Center. https://med.stanford.edu/news/insights/2025/01/microplastics-in-body-polluted-tiny-plastic-fragments.html

Lake, J. (2024, May 22). Future Trends in Biodegradable Plastic Technology. Bio-Tec Environmental. https://goecopure.com/future-trends-in-biodegradable-plastic-technology/

Lamichhane, G., Acharya, A., Marahatha, R., Modi, B., Paudel, R., Adhikari, A., Raut, B. K., Aryal, S., & Parajuli, N. (2022, May 26). Microplastics in environment: global concern, challenges, and controlling measures. International journal of environmental science and technology : IJEST. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9135010/

Leviker, K. (2024, December 3). Microplastics are not just in us, they are also in wildlife. https://pirg.org/articles/microplastics-are-not-just-in-us-they-are-also-in-wildlife/

Li, Y., Tao, L., Wang, Q., Wang, F., Li, G., & Song, M. (2023, August 10). Potential Health Impact of Microplastics: A Review of Environmental Distribution, Human Exposure, and Toxic Effects | Environment & Health. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/envhealth.3c00052

Malafeev, K. V., Apicella, A., Incarnato, L., & Scarfato, P. (2023, September 6). Understanding the Impact of Biodegradable Microplastics on Living Organisms Entering the Food Chain: A Review. Polymers. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10534621/

Myers, J., & North, M. (2025, February 19). Microplastics: Are we facing a new health crisis – and what can be done about it?. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/02/how-microplastics-get-into-the-food-chain/

Nyoni, H. (2025, February 4). Microplastics: Sources, health risks, and how to protect yourself. Institute of Energy and the Environment. https://iee.psu.edu/news/blog/microplastics-sources-health-risks-and-how-protect-yourself#:~:text=First%2C%20you%20can%20opt%20for,and%20ensuring%20effective%2C%20transparent%20solutions.

Readfearn, G. (2020, October 5). More than 14m tonnes of plastic believed to be at the bottom of the Ocean. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/oct/06/more-than-14m-tonnes-of-plastic-believed-to-be-at-the-bottom-of-the-ocean

Samantaroy, S. (2024, August 9). Humans Now Ingest Six Times More Microplastics Than in 1990. Health Policy Watch. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/humans-now-ingest-six-times-more-microplastics-since-1990/

Taylor, S. E. (2020, November 9). The Root of Microplastics in pPlants. PNNL. https://www.pnnl.gov/news-media/root-microplastics-plants