Introduction

Climate change is arguably the defining challenge of our time. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence that global warming threatens ecosystems, economies, and human well-being, public conversations often emphasize the role of individuals: these conversations mention reducing meat consumption, refusing single-use plastics, biking to work, or recycling at home. These actions areo obviously good, as they build awareness, create responsibility, and allow people to feel like they are contributing to a solution. However, while personal choices can reduce individual carbon footprints, they do not address the systemic drivers of climate change: fossil fuel dependence, industrialized agriculture, inefficient urban planning, and global economic structures that incentivize overconsumption.

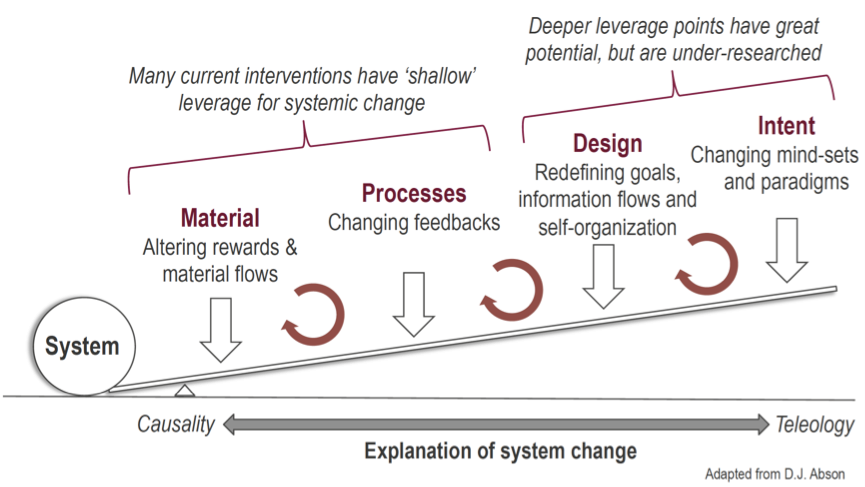

To achieve meaningful climate action, it is important to understand how individual behaviors and systemic interventions work together. While personal choices can change social norms and cause political pressure, large-scale changes in policy, corporate accountability, and infrastructure are what actually cause emissions to reduce. This blog argues that climate solutions require both approaches, with systemic change as the primary driver, and personal action as a complementary, reinforcing factor.

Why focus on Individuals?

It is not surprising that much environmental messaging focuses on individuals. Campaigns promoting household recycling, eco-friendly products, or plant-based diets are psychologically appealing, because they offer tangible actions that people can control, even though climate change can seem quite overwhelming. Installing a low-flow showerhead, refusing plastic straws, or composting at home may seem small, but these behaviors provide evidence of moral engagement and can give people a real sense of empowerment.

Human psychology suggests that actions that are concrete and directly controllable. Abstract systemic changes, like lobbying for renewable energy legislation or reforming industrial emissions, feel distant to ordinary people, who would rather do things that they feel they can control. Individual behaviors offer immediate feedback, social recognition, and a sense of accomplishment. So, campaigns and ideas that make sustainability seem like a personal moral responsibility appeal to our desire to “do something” in the face of uncertainty that is felt around the world.

However, these personal choices, while meaningful on an individual level, cannot actually reduce the emissions needed to prevent global warming. Research by Dietz et al. (2009) and Wynes & Nicholas (2017) show that even widespread adoption of high-impact behaviors, such as eliminating car use or shifting to plant-based diets, can only reduce U.S. emissions by a few percentage points over a decade. However, if we were to use systemic interventions, like transitioning energy grids to renewables, reforming transportation infrastructure, and enforcing industrial emissions standards, we can cut emissions by more than 50 percent in the same timeframe. This demonstrates how climate change is driven primarily by broader societal choices, not individual morality. Personal responsibility matters only if it can actually be similar as it aligns with broader changes made by the people in power.

Green Consumerism and the Illusion of Choice

The focus on personal responsibility is closely linked to green consumerism. Many people think that buying eco-friendly products, like reusable water bottles, biodegradable detergents, and sustainably produced clothing would help solve the climate crisis. While these choices are positive, scholars argue that they often reinforce the dangers of capitalism and overconsumption rather than actually reducing environmental harm in ways that matter.

Gleeson & Low (2020) describe sustainable consumption as a “fatal contradiction”: even green products require energy, raw materials, and distribution networks, all of which contribute to emissions. Dauvergne & Lister (2013) point out that corporate sustainability initiatives often function primarily as branding, making it seem as though environmental responsibility exists but doesn’t actually address the broader forces of society. Maniates (2001) highlights the “individualization of responsibility,” noting that these practices shift accountability from governments and corporations to individuals.

Also, eco-products are usually much more expensive, meaning they usually serve wealthier consumers while making it seem as though all of society is actively participating in buying these products. Green consumerism can also accidentally suggest that climate change is a matter of personal moral failure rather than structural reform, making it harder to see the areas where real power and influence lie.

Despite these limitations, individual actions are far from meaningless. They are broader cultural influences, and they create norms that influence political and corporate decision-making. Behavioral science shows that visible personal changes can shift social expectations and influence policy adoption. For example, when communities collectively adopt renewable energy, composting, or plant-based diets, policymakers and businesses take notice of the economic and cultural signals, often leading to systemic reforms (Mildenberger & Leiserowitz, 2017).

Case Study: Community Solar Programs

Community solar initiatives in Minnesota and Colorado allow residents to collectively invest in solar energy projects, even if they cannot install panels on their own homes. These programs combine individual participation with systemic investment, which create measurable reductions in carbon emissions while also resulting in public support for renewable energy policies. The community can see tangible results from their actions, which reinforces both personal and commitments to their communities.

Case Study: Plant-Based School Meals

The Los Angeles Unified School District introduced weekly plant-based meals in 2020, reaching over 600,000 students. A single student’s choice has minimal impact, but when institutionalized across an entire district, the policy produces significant emissions reductions. This illustrates how systemic interventions can scale individual behaviors, creating lasting cultural change.

Systemic Interventions: The Primary Engine of Change

While personal behaviors signal values and norms, systemic interventions drive the majority of emissions reductions. These include:

- Decarbonizing energy grids: Replacing coal, oil, and natural gas with renewable electricity.

- Transportation reforms: Expanding public transit, encouraging electric vehicle adoption, and designing bike-friendly cities.

- Building efficiency: Updating codes, retrofitting insulation, and electrifying heating systems.

- Industrial regulation: Implementing emissions standards, carbon pricing, and sustainable supply chains.

These interventions provide measurable reductions at scale, often far exceeding what is possible through personal behavior. For instance, fully decarbonizing the U.S. energy grid could reduce national emissions by over half in a decade, whereas even widespread individual behavior change would achieve only a fraction of that reduction (IPCC, 2022).

Case Study: Copenhagen, Denmark

Copenhagen is celebrated for its cycling culture, with over 60% of residents commuting by bike daily. This norm did not arise spontaneously—it is the result of systemic investments in protected bike lanes, infrastructure, and urban planning that prioritized non-motorized transit (City of Copenhagen, 2020). The city demonstrates how infrastructure and policy can shape behavior, making sustainable choices easy and culturally normative.

Case Study: Curitiba, Brazil

Curitiba implemented a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system in the 1970s, offering affordable, frequent, and reliable public transit. This system reduced private car use, cut emissions, and improved urban livability (Rojas-Rueda et al., 2016). Here again, systemic design created the conditions for individual choices to matter, reinforcing the link between policy and personal behavior.

Case Study: Germany’s Energiewende

Germany’s Energiewende initiative shows how policy-driven systemic reform can transform energy production. Feed-in tariffs, subsidies for renewable adoption, and a gradual coal phase-out have significantly increased renewable electricity output since 2000. While politically and economically complex, these reforms demonstrate how systemic interventions can achieve measurable, large-scale emissions reductions (Agora Energiewende, 2021).

The Challenges of Renewable Energy

While renewable energy is essential, it comes with several trade-offs. Solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries require resource-intensive mining for lithium, cobalt, and nickel. Mining operations can cause environmental degradation, pollute water systems, and harm vulnerable communities (Sovacool et al., 2020; Vidal et al., 2013).

Life-cycle analyses, however, show that renewable energy produces significantly fewer emissions over its operational life compared to fossil fuels (Hertwich et al., 2015). The challenge lies in responsible sourcing, ethical oversight, and international cooperation, ensuring that the shift to low-carbon energy does not replicate existing social and environmental injustices.

Counterarguments and Critiques

Several critiques complicate the debate between individual and systemic responsibility:

- “Individual change will naturally produce systemic change.” While individual behavior matters culturally, evidence shows that systemic reforms achieve far greater emissions reductions (Dietz et al., 2009).

- “Systemic reforms are slow and politically challenging.” True, but long-term benefits—including emissions reductions, public health improvements, and infrastructure resilience—outweigh short-term costs.

- “Climate policy limits freedom.” Effective regulation protects communities from extreme weather, pollution, and food insecurity. Infrastructure improvements expand opportunities for sustainable living.

Equity concerns: Systemic reforms can disproportionately affect low-income populations if poorly designed. However, policies like subsidies, incentives, and accessible public transit can ensure equitable benefits while reducing emissions.

A Combined Approach: Strategic Individual Action and Systemic Reform

The most effective climate change ideas use individual behaviors with systemic reforms. Personal choices show values, reinforce cultural norms, and engage communities, while systemic interventions provide the structural foundation for measurable reductions.

Examples of this combination include:

- Voting and advocacy: Electing climate-conscious leaders, joining activism campaigns, supporting legislation.

- Sustainable consumption: Reducing waste, conserving energy, and adopting plant-based diets.

- Corporate pressure: Supporting companies with transparent sustainability practices.

When systemic reforms provide infrastructure—public transit, building codes, renewable energy access—individual action becomes effective and possible.

Case Study: Community Solar and Citizen Participation

Community solar programs show how policy and personal choice intersect. Residents invest together in solar projects, gaining both measurable carbon reductions and visible proof of environmental commitment (U.S. Department of Energy, 2021). These programs also show that individual participation can create systemic reforms and foster long-term cultural change.

Case Study: Plant-Based School Meals

Furthermore, adoption of plant-based meal programs in schools show the combination between policy and individual choice. Students participating in weekly vegan meals may see minimal impact individually, but systemic implementation across entire districts scales behavior, promotes culture change, and produces measurable environmental benefits (Los Angeles Unified School District, 2020).

Rethinking Sustainability as Moral Responsibility

Sustainability is often framed as a set of personal moral choices: “Recycle, reduce meat consumption, avoid plastics.” While moral engagement is valuable, this framing risks misdirecting responsibility away from the structural levers that drive emissions. Climate change originates in industrial systems, infrastructure, and economic incentives—not solely in individual behaviors.

An effective environmental ethic should emphasize collective responsibility, strategic engagement, and institutional accountability. Personal actions matter most when connected to systemic reforms, creating a coordinated response that aligns moral intention with measurable impact.

Conclusion: Coordinated, Evidence-Based Action

Climate action also requires both individual and systemic approaches, but systemic reform must take priority. Personal behaviors—while symbolically, socially, and morally important, cannot substitute for large-scale policy changes, corporate accountability, and infrastructure redesign.

The most effective strategies combine:

- Systemic interventions: Decarbonized energy, transportation reform, building efficiency, industrial regulation.

- Strategic individual behaviors: Voting, advocacy, sustainable consumption, and consumer influence.

- Cultural reinforcement: Visible actions that signal values, create social norms, and motivate policy adoption.

By combining individual efforts and systemic reforms, society can achieve possible emissions reductions, distribute responsibility equitably, and create a culture that prioritizes sustainability. The climate crisis cannot be solved by guilt or moral aspiration alone, because it requires coordinated, evidence-based action.

Part 2: Expanding the Climate Conversation – Justice, Innovation, and Global Action

While individual actions and domestic systemic changes are important, climate change is not just a local issue, it is global, deeply inequitable, and also deeply involved with social justice.

Climate Justice: Who Bears the Brunt?

One of the clearest lessons from global climate research is that those who contribute the least to climate change often suffer the most. Small island nations, like Tuvalu and Kiribati, face rising sea levels that threaten their existence. Communities in sub-Saharan Africa are experiencing droughts that disrupt food and water access, despite historically low greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, wealthier nations and industrial corporations, like the US, which are responsible for the majority of historical emissions— don’t have to deal with similar consequences.

This imbalance raises urgent questions about ethics and responsibility. For meaningful climate action, policy cannot just reduce emissions, it must discuss inequality, create change in vulnerable regions, and show that those most affected have a voice in decisions. Personal choices, while still relevant, cannot solve these systemic and global inequities.

Case Study: Bangladesh and Resilient Infrastructure

Bangladesh, a low-lying country with a dense population, has experienced increasingly severe cyclones and flooding. While individuals can build raised homes or use sandbags, these measures are not helpful alone. Government investment in flood barriers, early warning systems, and resilient infrastructure is essential. International aid and climate financing further support adaptation, demonstrating that systemic intervention at multiple scales is critical for protecting vulnerable populations.

Global Coordination and International Policy

Climate change transcends national borders. The emissions from one country affect the entire planet, making international cooperation non-negotiable. Agreements like the Paris Climate Accord exemplify how countries can commit to collective action, although enforcement remains a challenge.

Individuals can influence this level indirectly. Public demand, activism, and cultural engagement can put pressure on national leaders to take climate action. Greta Thunberg’s Fridays for Future movement illustrates this power: her school strikes began as a personal initiative but became a global movement, inspiring millions and influencing political agendas worldwide.

Example: Cross-Border Renewable Energy

Some countries are already experimenting with collaborative energy projects. For instance, the Desertec initiative in North Africa aimed to generate solar power for Europe, creating renewable energy infrastructure that benefits multiple nations. While individual advocacy cannot directly build solar farms in another continent, global coordination—spurred by public pressure, policy commitments, and economic incentives—amplifies both systemic and individual efforts.

Innovation as a Lever for Systemic Change

Technology is one of the most promising tools in the fight against climate change, but it must be paired with policy, investment, and equitable access. Innovation can reduce emissions dramatically when supported by systemic frameworks.

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)

Carbon capture and storage technologies have the potential to remove CO₂ from the atmosphere at scale. But adoption depends on regulation, financial incentives, and industrial participation. While individuals can reduce their reliance on carbon-intensive activities, systemic investment in CCS is what allows the technology to reach a scale that truly matters.

Vertical Farming and Urban Agriculture

Urban agriculture, including vertical farming, reduces the carbon footprint of food by cutting transportation and land-use impacts. A single household growing vegetables contributes minimally, but when cities implement vertical farms that feed thousands, emissions reduction becomes substantial. Policies supporting land use, subsidies, and infrastructure are critical for turning these innovations into systemic solutions.

Education and Public Awareness

Education is a powerful systemic lever because it shapes culture, informs behavior, and builds public pressure for policy change. Students who learn about climate systems, energy infrastructure, and industrial emissions are better equipped to make meaningful decisions and advocate for reforms.

Case Study: Finland’s Climate Curriculum

Finland integrates climate literacy across grade levels, emphasizing systemic thinking and civic engagement. Students not only learn to recycle or save energy but also understand how policy, technology, and societal structures affect climate outcomes. Over time, education empowers citizens to participate in climate governance, creating a society-wide multiplier effect for systemic action.

Education also helps counter the misleading narrative that individual behavior alone can save the planet. Understanding systemic complexity allows individuals to take action strategically, rather than in isolation.

Cultural Influence and Media

Media, art, and storytelling shape perceptions of responsibility and urgency. Documentaries like Our Planet or viral social media campaigns about plastic pollution or wildfires provide vivid, relatable narratives that influence culture. While watching a documentary doesn’t reduce emissions directly, it alters social norms, sparks activism, and pressures policymakers and corporations.

Example: Social Media and Corporate Accountability

Campaigns like #StopPlasticPollution or #ClimateStrike mobilize millions, creating tangible pressure on businesses to adopt sustainable practices. Individuals amplify systemic change through digital engagement, which communicates public demand to governments and corporations alike.

Policy Instruments and Systemic Leverage

Systemic change requires policies that create the conditions for emissions reductions at scale:

- Carbon pricing: Encourages businesses to reduce emissions economically.

- Renewable energy mandates: Ensure large-scale adoption of low-carbon energy sources.

- Transportation investments: Support electric vehicles, public transit, and bike infrastructure.

- Efficiency standards: Reduce emissions across buildings and industries.

Without these policies, individual actions remain isolated. Driving an electric vehicle only reduces emissions significantly if the grid itself is decarbonized. Similarly, composting programs succeed when municipalities provide collection infrastructure. Systemic frameworks enable personal behavior to translate into measurable impact.

Equity and Distribution of Responsibility

Effective climate policy must distribute responsibility fairly. Placing the entire burden on individuals, particularly those with limited resources, is neither just nor effective. Systemic solutions allow for equitable participation: citizens can adopt sustainable behaviors, but corporations and governments shoulder the larger responsibilities of industrial emissions, infrastructure, and global trade.

Example: Environmental Racism in the U.S.

Communities of color often live near highways or industrial plants, exposing residents to higher levels of pollution. Individual behaviors like recycling do little to mitigate this risk. Policy interventions, such as stricter emissions standards, clean-up initiatives, and zoning reform, are essential. Equitable climate action addresses both emissions and social justice.

The most effective climate solutions occur at the intersection of personal behavior, systemic reform, and cultural engagement:

- Individual actions as signals: Citizens choose renewable energy, reduce waste, and participate in advocacy.

- Systemic interventions as enablers: Policies, investments, and regulations create the conditions for large-scale change.

- Cultural reinforcement: Education, media, and social norms sustain long-term adoption and influence public opinion.

When aligned, these three layers form a positive feedback loop, magnifying each other’s impact. A city-wide bike lane program, for example, combines policy infrastructure, individual participation, and cultural acceptance to create measurable environmental benefits.

Practical Takeaways for Action

- Vote and advocate: Support leaders and policies prioritizing climate mitigation and adaptation.

- Make strategic personal choices: High-impact behaviors, like reducing energy use or choosing renewable sources, amplify systemic change.

- Engage culturally: Share knowledge, participate in campaigns, and contribute to a climate-conscious culture.

- Support innovation: Encourage and invest in new technologies that reduce emissions, but also push for ethical sourcing and equitable access.

- Demand justice: Ensure climate policies include vulnerable communities and address inequities locally and globally.

Part 3: Beyond Policy – Communities, Corporations, and the Power of Storytelling

Behavioral Economics and Climate Action

Even when policies exist, human behavior doesn’t always follow logic. People want to act sustainably, but convenience, habits, and social norms often get in the way. Behavioral economics helps explain this gap, showing how people respond more strongly to social cues and defaults than to abstract moral appeals (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). For example, studies show that labeling energy use with comparisons to neighbors (“You use 15% more electricity than your neighbors”) encourages conservation more effectively than technical information alone (Allcott, 2011). Similarly, default options—like automatically enrolling employees in green energy programs unless they opt out—dramatically increase participation (Pichert & Katsikopoulos, 2008). The key takeaway is that systemic structures and small behavioral nudges can make individual actions more effective, combining policy, psychology, and culture to achieve measurable results.

Communities are where individual choices meet collective power. Neighborhood programs, local cooperatives, and community gardens offer practical ways to reduce emissions while fostering social cohesion and political influence (Ostrom, 2010).

Case Study: Community Solar in California

Community solar projects allow households that can’t install panels on their rooftops to buy shares in a larger solar farm. Individually, participants reduce their carbon footprint modestly—but together, they create a financial and political signal that supports renewable energy adoption. Local governments often notice these efforts and may expand incentives, creating a feedback loop between personal action and systemic change.

Case Study: Eco-Villages and Cooperative Living

Eco-villages in Europe and North America demonstrate sustainable living at scale. Residents share resources, reduce waste, and adopt renewable energy collectively. While individual households make choices like installing solar panels, the community context multiplies their impact, showing that sustainability thrives where people collaborate intentionally. (U.S. Department of Energy, 2023).

Corporate Accountability

Corporations are major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, often dwarfing individual footprints. Yet businesses are sensitive to consumer demand, shareholder pressure, and public perception, making them a critical leverage point for climate action. (CDP, 2017).

Example: Patagonia and Ethical Business Models

Patagonia has built its brand on environmental stewardship, including product recycling programs and transparent supply chains. Consumers support the company not just because of the products but because their purchases align with a larger systemic effort. Companies like Patagonia demonstrate that business decisions can reinforce both personal and systemic climate action. (Hainmueller et al., 2015).

Example: Fossil Fuel Divestment

Universities, pension funds, and large investors increasingly divest from fossil fuels, pressuring companies to adopt cleaner energy practices. While a single individual can’t force a corporation to change, coordinated financial and consumer pressure alters corporate priorities, which can result in measurable emission reductions at scale. (Ansar et al., 2013).

Storytelling and Climate Engagement

Humans respond to stories. Numbers and charts explain the problem, but narratives move people to care, act, and advocate. Climate storytelling—from documentaries to novels to social media campaigns—shapes cultural understanding and motivates systemic change.

Example: An Inconvenient Truth

Al Gore’s documentary translated complex climate science into a compelling story, raising global awareness. While viewers didn’t directly change policies themselves, the cultural impact supported advocacy, policy discussion, and personal behavior changes, demonstrating the power of storytelling as a bridge between science and action (Nolan, 2010).

Example: Social Media Climate Activism

Digital campaigns, from viral climate memes to Twitter campaigns, allow individuals to signal values collectively, making the climate crisis culturally salient. Online visibility creates pressure for corporate and governmental accountability, proving that storytelling is a tool that connects personal, community, and systemic efforts. (Pearce et al., 2019)

Practical Community-Level Actions

For those looking to make a difference without waiting for national policy:

- Organize local cleanups or tree-planting drives—visible, tangible community impact.

- Create or join cooperative renewable energy projects—sharing infrastructure reduces barriers.

- Advocate for local green policies—from zoning reforms to bike lanes, community lobbying drives systemic change.

- Use social media to amplify climate education—share stories, data, and campaigns to build cultural momentum.

- Support local sustainable businesses—encouraging corporate accountability while fostering community resilience.

These initiatives demonstrate that systemic change and personal action are not mutually exclusive—they reinforce each other.

The Feedback Loop Between Individuals, Communities, and Systems

When individuals engage in meaningful personal actions within community frameworks, their impact scales. Communities can push local governments toward systemic reforms, influence corporate practices, and model sustainable living for broader society. In turn, systemic policies and corporate accountability make individual and community efforts more effective.

For example, a city that invests in robust public transit enables residents to drive less. Communities that organize around renewable energy create demand signals that encourage corporations to expand clean energy solutions. Culture and storytelling amplify both, creating a network of influence across scales.

Behavior, Culture, and Policy: A Unified Approach

The challenge of climate change requires multi-layered strategies that integrate:

- Behavioral insights: Nudging individuals toward high-impact actions

- Community engagement: Mobilizing collective efforts for visibility and influence

- Corporate responsibility: Using market and social pressure to reduce industrial emissions

- Cultural storytelling: Shaping social norms and inspiring systemic change

- Policy reform: Implementing regulations and infrastructure that maximize impact

No single approach is sufficient, but combined, they create a powerful ecosystem for climate action, where each layer reinforces the others.

Conclusion: From Awareness to Action

By now, it’s clear that climate solutions are more than personal choices or policy mandates—they are a combination of individual, community, corporate, and systemic efforts. Individual action signals values, community action multiplies impact, corporate accountability ensures industrial reform, and storytelling shapes culture and advocacy. Together, these layers form the backbone of effective climate action.

The climate crisis is enormous, urgent, and complex—but it is not hopeless. Strategic, coordinated action across scales ensures that personal efforts are meaningful, systemic interventions are supported, and the next generation inherits a sustainable, equitable planet.

We live in a world where individual behavior matters most when it connects to the systems and communities around us. Reusable bags, compost bins, or plant-based meals are only the beginning. The real work lies in collective action, systemic reform, and a culture that values sustainability as a shared responsibility.

References (APA 7th Edition)

Dauvergne, P., & Lister, J. (2013). Eco-business: A big-brand takeover of sustainability. MIT Press.

Dietz, T., Gardner, G. T., Gilligan, J., Stern, P. C., & Vandenbergh, M. P. (2009). Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(44), 18452–18456. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0908738106

Gleeson, D., & Low, N. (2020). Green consumption: The fatal contradiction of sustainable development. Sustainability, 12(14), 5653. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145653

Hertwich, E. G., Gibon, T., Bouman, E. A., Arvesen, A., Suh, S., Heath, G. A., … & Shi, L. (2015). Integrated life-cycle assessment of electricity-supply scenarios confirms global environmental benefit of low-carbon technologies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(20), 6277–6282. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1312753111

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2022). Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3

International Energy Agency. (2021). The role of critical minerals in clean energy transitions. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions

Maniates, M. F. (2001). Individualization: Plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Global Environmental Politics, 1(3), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1162/152638001316881395

Mildenberger, M., & Leiserowitz, A. (2017). Public opinion on climate change: Is there an economy–environment tradeoff? Environmental Politics, 26(5), 801–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1322275

Prothero, A., Dobscha, S., Freund, J., Kilbourne, W. E., Luchs, M. G., Ozanne, L. K., & Thøgersen, J. (2011). Sustainable consumption: Opportunities for consumer research and public policy. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 30(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.30.1.31

Sovacool, B. K., Ali, S. H., Bazilian, M., Radley, B., Nemery, B., Okatz, J., & Mulvaney, D. (2020). Sustainable minerals and metals for a low-carbon future. Science, 367(6473), 30–33. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz6003

United Nations Environment Programme. (2020). Emissions gap report 2020. https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2020

Vidal, O., Goffé, B., & Arndt, N. (2013). Metals for a low-carbon society. Nature Geoscience, 6(11), 894–896. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1993

White, K., Habib, R., & Hardisty, D. J. (2019). How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. Journal of Marketing, 83(3), 22–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919825649

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (GPT-5.2) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/

Wynes, S., & Nicholas, K. A. (2017). The climate mitigation gap: Education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environmental Research Letters, 12(7), 074024. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541

World Bank. (2020). Minerals for climate action: The mineral intensity of the clean energy transition. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/503561468980941015

Gore, A. (2006). An inconvenient truth: The planetary emergency of global warming and what we can do about it. Rodale Books.

Thunberg, G. (2019). No one is too small to make a difference. Penguin.

Fridley, D., & Zheng, N. (2019). Urban energy use in China: The role of cities in systemic energy and climate policy. Energy Policy, 132, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.05.012

Friedman, L., & Tabuchi, H. (2021, July 12). Fossil fuel divestment gains steam among universities and funds. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/12/climate/fossil-fuel-divestment-universities.html

Hawken, P. (Ed.). (2017). Drawdown: The most comprehensive plan ever proposed to reverse global warming. Penguin.

C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. (2020). Climate action in cities: Lessons from global urban initiatives. https://www.c40.org/researchEuropean Commission. (2021). Behavioral insights and nudging for climate action. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/behavioral-insights

Allcott, H. (2011). Social norms and energy conservation. Journal of Public Economics, 95(9–10), 1082–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.03.003

Ansar, A., Caldecott, B., & Tilbury, J. (2013). Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: What does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets? University of Oxford, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment.

Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). (2017). The carbon majors report 2017. CDP Worldwide.

Global Ecovillage Network. (2018). Ecovillages: Lessons for sustainable community development.

Hainmueller, J., Hiscox, M. J., & Sequeira, S. (2015). Consumer demand for fair trade: Evidence from a multistore field experiment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(2), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00467

Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12–23.

Nolan, J. M. (2010). “An Inconvenient Truth” increases knowledge, concern, and willingness to reduce greenhouse gases. Environment and Behavior, 42(5), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509357696

Ostrom, E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.004

Pearce, W., Niederer, S., Özkula, S. M., & Sánchez Querubín, N. (2019). The social media life of climate change: Platforms, publics, and future imaginaries. WIREs Climate Change, 10(2), e569. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.569

Pichert, D., & Katsikopoulos, K. V. (2008). Green defaults: Information presentation and pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.09.004

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

U.S. Department of Energy. (2023). Community solar basics. Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.