Introduction

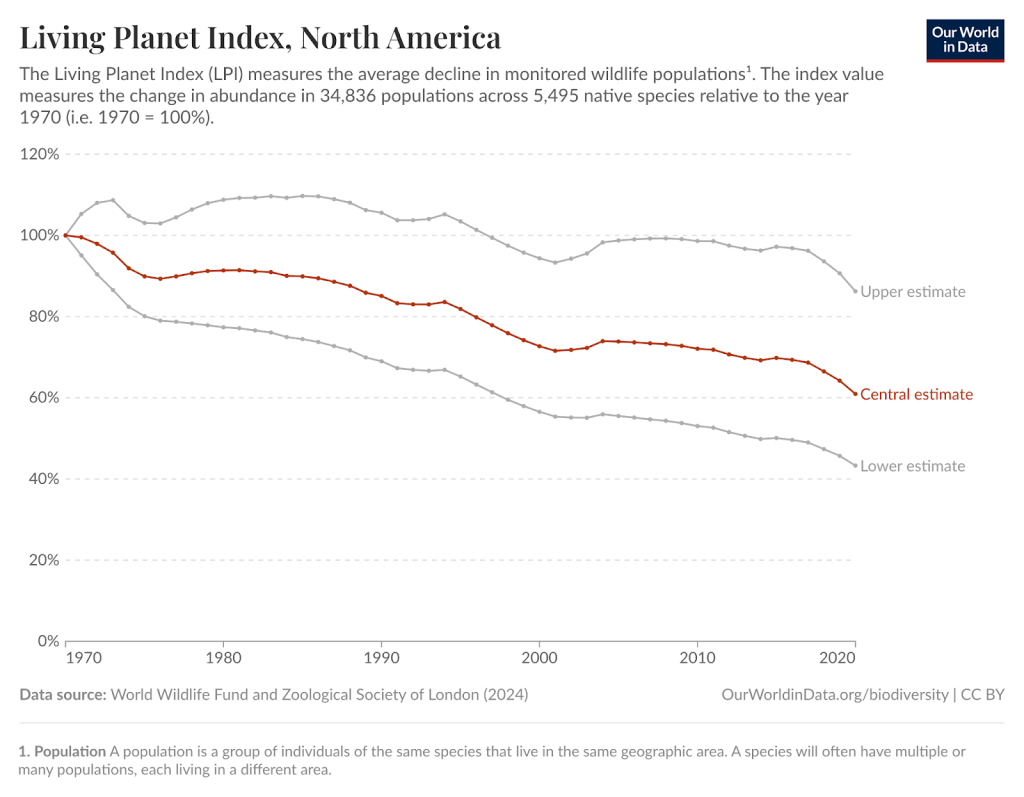

Since the first colony ship arrived at Jamestown, the United States has suffered from a horrific rate of environmental change brought on by our reckless systems of agriculture, extraction of natural resources, and urban expansion, with one of the most notable impacts being a massive drop in national biodiversity due to habitat loss. This issue has only worsened in the past half-century as we have continued to expand in industry, agriculture, and housing in order to keep up with a growing population, and begun to feel the effects of human-induced climate change (Rosenberg et al., 2019). So while we may no longer be clear cutting massive swathes of land or methodically eradicating America’s keystone species as our colonial forefathers did, we are still facing the same core issue of habitat loss and national biodiversity decline (Steinberg, 2002/2019). In fact, through the Living Planet Index, provided by the WWF and Zoological Society of London, we can see that North American biodiversity has been on a steady decline, with the lower estimate putting us at a 60% loss in biodiversity since 1970, as can be seen in the graph below (Ritchie et al., 2021).

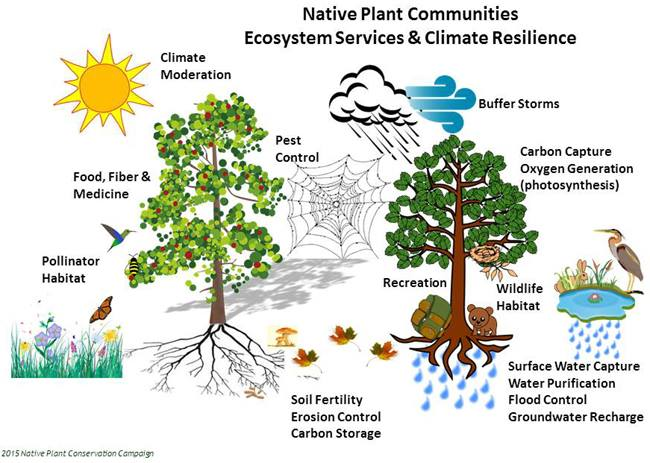

But what does the presence of all these different kinds of native wildlife and plant life have to do with human wellbeing—or, better yet, our lawns? As it turns out, it has quite a bit to do with both. Human proximity to green spaces and plant life has been shown to improve mental well-being, air quality, and decrease soil erosion. The presence of birds supports a $75 billion birdwatching industry, and the basic ecosystem services these organisms provide are what allow us to survive in the first place (Missouri Department of Conservation, 2024).

So how do we bring these ecosystems and the services they provide closer to us in a way that benefits everyone? One solution may be small-scale urban rewilding, a process where an individual or group of people takes a small piece of urban/suburban land and dedicates it to reviving and supporting the larger modern ecosystem we live as a part of. Yards provide a perfect template for small scale rewilding projects which have been scientifically proven to drive up native insect populations, which in turn attract and support native bird populations, which in turn support native plant life, creating a natural cycle which helps to rebuild the essential ecosystem we paved over (Finnerty et al., 2025; Török et al., 2021; Winkler et al., 2024). Despite these upsides, some are naturally skeptical of the ability of small-scale rewilding to deliver on its promises or worse, fear it will harm them personally by devaluing their homes, inviting in pests, increasing the chance of unwanted animal encounters, or worse yet, creating further ecological damage through improper implementation. Nonetheless it would seem that if enough people participated in small-scale rewilding on their own property, we could make a real difference in combating this national loss of essential biodiversity as collectively each property collectively forms “an interconnected ecological network”(Tallamy, 2019).

What is Rewilding?

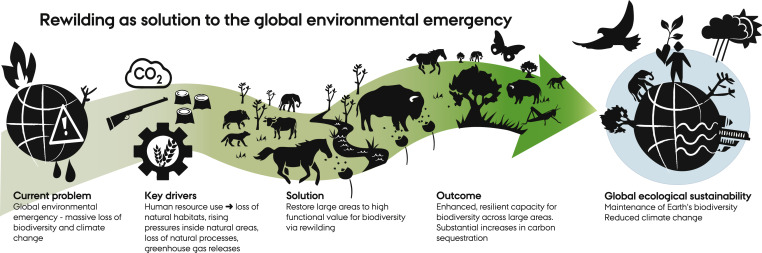

So rewilding can offer us a lot as a solution to modern biodiversity loss, but what in the world is it? Well, that depends on who you ask. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, rewilding is the “process of restoring an area of land to its natural uncultivated state.” According to critics of the practice, such as Dr. Irma Allen, a well-regarded ecologist and vocal environmentalist, rewilding is “conservation by dispossession” and a potential extension of American ecological imperialism (Allen, 2016). According to other scientific professionals who see promise in rewilding, it is “a more proactive approach to combat unprecedented faunal declines and extinctions” (Finnerty et al., 2025). In the context of this article, however, rewilding means something slightly different. Here, we define rewilding as the methodical reintroduction of native species to an already disturbed landscape with the intention of expanding preexisting modern natural habitats within a specific ecological region. The specificity of this definition has been chosen to preemptively combat the concern that this article is promoting the reckless reintroduction of species, or worse, the ecological imperialism brought on by attempting to replicate a “pristine” form of nature. The goal here is not to build our ideal of what nature should be, but rather to take already disturbed land and try to slowly transition it into a landscape more similar to the immediately surrounding natural habitat in a way that benefits native wildlife on a multi-trophic level (across the whole food chain). Now that it is clear what the word rewilding means within the context of both this paper and the larger conversation at hand, we can begin to pick apart what rewilding means in practice.

How Does Rewilding Look in Practice? Large Scale Rewilding

In the history of its application, rewilding has largely been confined to nature reservations far away from urban centers, with the goal of restoring that area to a historical ideal. This application of rewilding can be seen in areas such as Yellowstone, where ecologists and conservationists are attempting to reintroduce specific species such as grey wolves, which were removed by earlier misguided efforts at game conservation (Steinberg, 2002/2019). The central idea seen here in “traditional” rewilding (introducing poorly selected species to a fundamentally changed environment in the hopes of rekindling a lost ecological niche for human benefit) is fundamentally rooted in the idea of a “pristine” nature; a nature which functions separately from humanity and will return to a set state of ecological stability and natural wonder if simply left to its own devices. “Pristine” nature does not exist. The basis of how we view nature has historically been largely anthropocentric, placing humanity above nature rather than as a working part of the natural ecosystem that is life itself (Steinberg, 2002/2019). This view of humanity as separate from nature and of nature being a tool for human conquest is the very ideal that has placed us in the position of even needing rewilding in the first place. It was what led to the mass deforestation of the Midwest in the late 1800s as industrialization swept the nation. It was what led to the ecological collapse of the Kaibab plateau in Arizona during the 1910s as America’s top conservationists waged an all-out war of annihilation on the nation’s predators. This eradication campaign included the aforementioned grey wolf, whose absence led to an overpopulation of deer, which then starved themselves by overgrazing everything within their range (Steinberg, 2002/2019). It was also this ideology that led to the failure that was the original rewilding effort of the Dutch nature reserve Oostvaardersplassen during the early 2000s-2010. During this project, shortsightedness surrounding the introduction of new species to more closely fit what the area “should have been” if not for human influence, led to a situation similar to that seen in the Kaibab plateau. Except, this time it led to the extinction of 22 rare bird species within the area, the death of “1,613 grazing species,” and the conversion of the area into a grassland completely unlike the mixed wetland it was before (Gerretsen, 2025). Thankfully, we have been able to largely reverse this damage. So clearly the “traditional” idea of rewilding is deeply flawed, but not all large-scale rewilding has been conducted with this philosophy of pristine nature in mind.

These two photos show the damage caused by the failed rewilding of Oostvaardersplassen. The left image is from 1984 before rewilding efforts began whereas the right image comes from the 2017-2018 period of ecological collapse and mass starvation caused by overgrazing which followed the reintroduction of several grazing species as part of the rewilding project. The most alarming aspect of these images is the loss of wetlands caused by this reintroduction effort (Gerretsen, 2025).

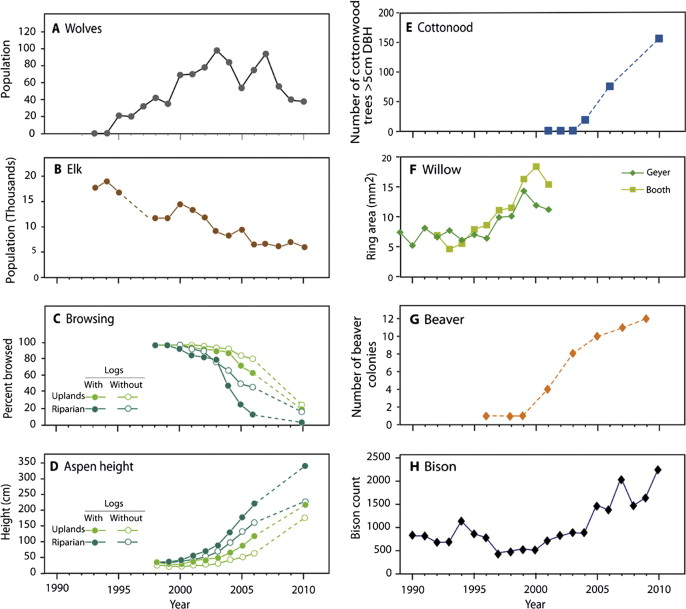

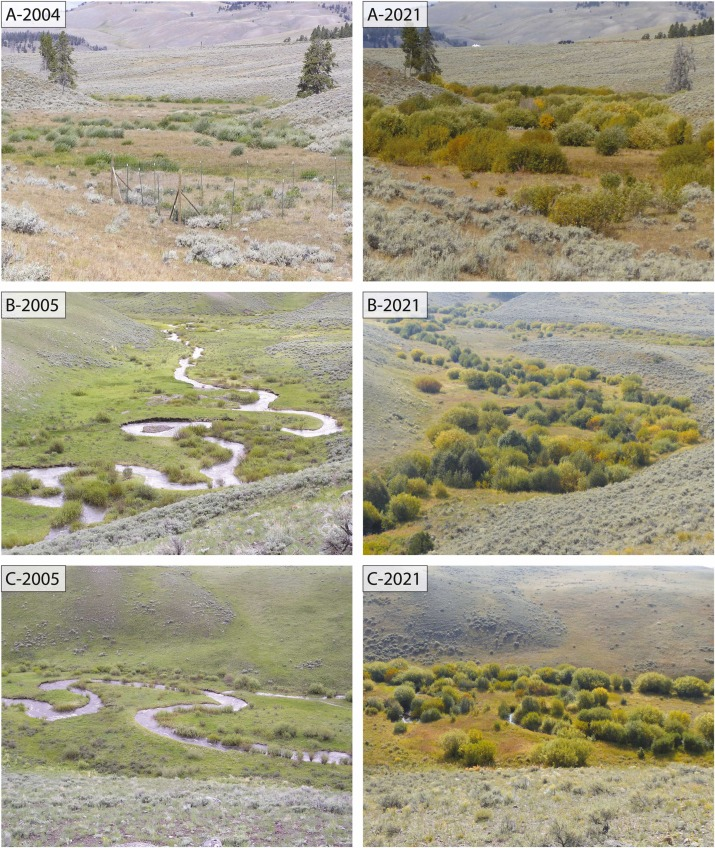

What wasn’t mentioned in the earlier example of Yellowstone’s reintroduction of wolves is that, although it does play off of this pristine myth in the sense that it seeks to return the park to a certain environment that was lost, the current park service conducting the actual rewilding efforts are under no illusions that the park was ever any kind of untouched natural paradise and are being very deliberate in the reintroduction of specifically wolves. They are not trying to completely transform an environment to fit their ideals for what it should be; instead, they are taking great care to understand both the past and current ecology of the region and to reintroduce the keystone species that regulate that ecosystem. This ecological focus is the key idea of more modern rewilding efforts and has had great success, especially within the Yellowstone project where the careful reintroduction of wolves has led to stable natural population rises in other keystone species such as beavers. Additionally, the presence of wolves has helped to solve the issue of food scarcity caused by elk overgrazing, as elk are forced to change feeding locations in order to avoid wolf predation. This same movement of herbivores motivated by the presence of wolves has also allowed other plantlife to return, including cottonwood trees, aspens, and willows (Farquhar, 2023; Ripple & Beschta, 2012). The benefits of this ecological cascade can be seen in the following figures.

The graph shown on the left here charts population growth among key Yellowstone species since the reintroduction of wolves while the photographs on the right shows the growth of willows along a riverbank as well as the recession of said river (Ripple & Beschta, 2012; Ripple et al., 2025)

As exemplified in Yellowstone’s wolf project, large-scale rewilding can be quite effective in exciting ecological regeneration within a region over several decades when those rewilding efforts are focused on a scientific understanding of the existing ecology of the region rather than a human-generated ideal for what that region should be. That said, large-scale rewilding has several limitations. While large-scale rewilding is theoretically ideal, it is very difficult to properly implement, especially in areas where people are active, such as near agricultural, suburban, or urban spaces, rather than pre-existing natural reserves such as national parks. It also requires a huge level of funding. For example, the Yellowstone wolf project was predicted to require over $3 million (about $6.5 million today) for only the first five years of the project when it began in 1994, and since then, costs have only grown. Furthermore, any large-scale effort requires support from both the wider public as well as direct support from several agencies within the federal government, and the bureaucracy and workforce necessary for sustained work to actually get anywhere (Ten Years of Yellowstone Wolves, 1995). Large-scale rewilding is not the only solution to the American biodiversity crisis; it must be augmented by further action because of these limitations.

Urban Rewilding

As mentioned previously, one of the leading causes of the avian biodiversity crisis is simply habitat loss due to the expansion of human-inhabited spaces, whether that be in the form of cities, suburbs, industrial parks, or wider urban sprawl. In order for humans to expand their habitat, the habitat of others must be removed. Urban rewilding is a modified form of rewilding focused on turning unused space in urban landscapes into a viable habitat for other species. It has been accredited with successfully increasing biodiversity in urban areas. In the US alone, urban rewilding can be accredited with restoring the populations of peregrine falcons, relict leopard frogs, and San Francisco forktails (a species of damselfly) within large urban centers such as Los Angeles and San Francisco (Finnerty et al., 2025). The most basic and common form of rewilding we see in urban spaces is the creation of parks and other “green spaces”, spaces which simply block out an area of urban landscape to serve as plantbeds (Standish et al., 2012). These forms of urban rewilding are generally well-received and supported by the public but tend to fall short in their ability to actually support wildlife due to the cultivated nature of such places and how difficult it is for terrestrial fauna to navigate through urban landscapes (Standish et al., 2012). Despite its shortcomings, urban rewilding is still remarkably better than nothing and could likely be easily improved by adding more native plants in landscaped areas such as parks. So while urban rewilding has a much smaller impact on biodiversity than the large-scale rewilding of something like a national park, it still has a noticeable impact, and the ideas behind it can be extended to other areas where these restraints around public support and funding are less prevalent, namely the suburbs.

Suburban Small Scale Rewilding

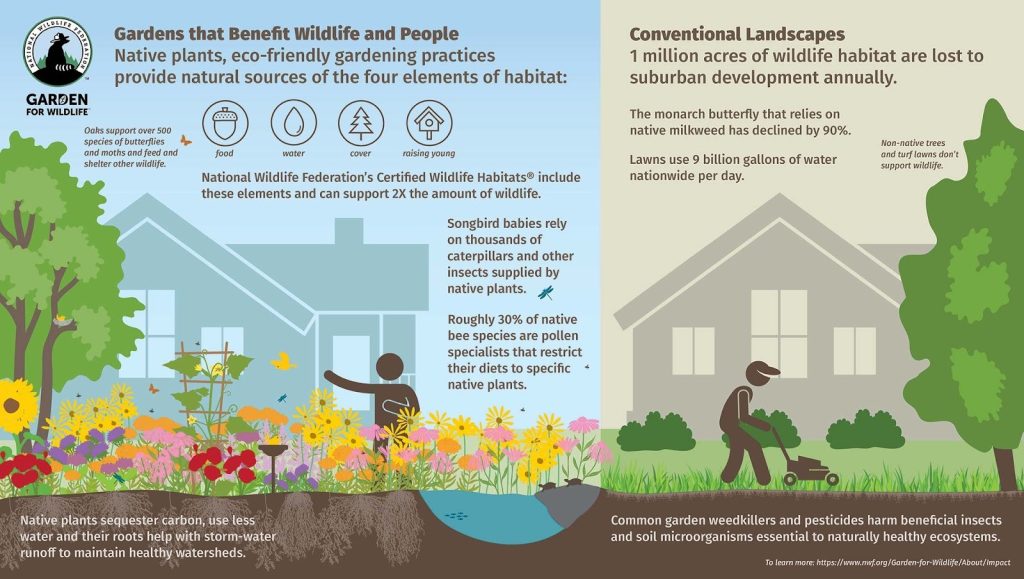

The easiest way to get around the limitations of government support, inadequate funding, and the time it takes for organizations to turn plans into action is surprisingly simple. Instead of solely relying on the government or other large organizations to source funding and draft plans, we can scale the operation down and place responsibility in the hands of individuals. Following in line with urban rewilding’s idea of repurposing unused space, we as individuals can evaluate the spaces we occupy and identify areas that can be repurposed for rebuilding habitat. Lawns, balconies, rooftops, even fences and building walls, can be repurposed into useful habitat through a modified process of rewilding. Since lawns essentially form “ecological dead zones” that provide virtually no food or shelter for wildlife, and serve no other functional purpose beyond aesthetics, small-scale rewilding within a suburban context consists primarily of the replanting of lawn space with local native plants chosen specifically to mirror the surrounding current wilderness environment (Tallamy, 2019).

Rewilding on this scale does not aim to fully restore an area of land to a functional wilderness ecosystem, nor does it potentially limit the use of the space in the way a city park might. Since it occurs on land that is a part of an individual’s living space, the goal of small-scale suburban rewilding is to create a space that can be successfully cohabited by both humans and a variety of native organisms on multiple trophic levels. This form of rewilding looks more like a somewhat unkept garden rather than the proper wilderness one might be tempted to imagine, and the all too common American lawn is the perfect canvas. Small-scale rewilding has already been proven effective in increasing biodiversity when managed correctly, and if enough people used at least a portion of their land for this purpose, it could make a real impact (Török et al., 2021). But how do we actually go about creating this kind of environment?

How to Rewild Your Lawn

Rewilding begins first with a thorough understanding of your local ecology and environment, and second with plants. As can be seen with the prior examples of the Kaibab plateau and Oostvaardersplassen, any misinformed or improperly executed form of environmental management, such as rewilding, can cause horrific ecological damage, so it is essential to be properly versed in the ecology of your immediate surroundings. Thankfully, there are a plethora of government and civilian organizations within the rewilding space who work with entomologists, botanists, ecologists, and horticulturalists in order to create resources to help people find out what they should plant to support their local species. But why start with plants? Plants provide the foundation for an ecosystem in that they provide both food and shelter for a variety of species across trophic levels.

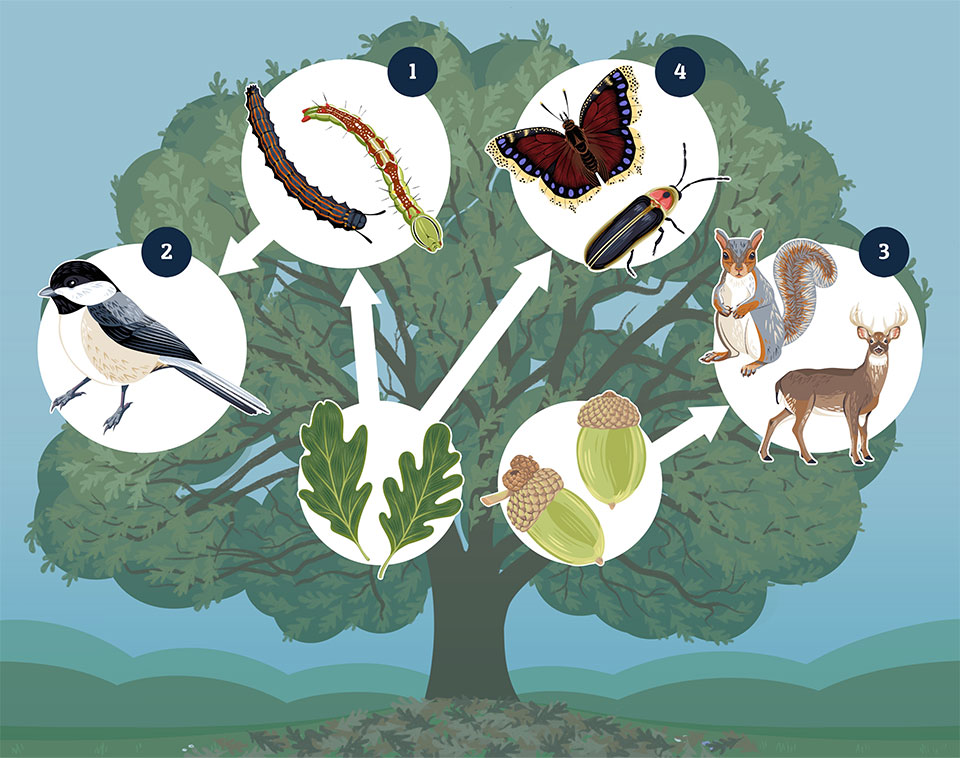

For example, an oak tree not only provides habitat for birds, arboreal mammals, and all kinds of insects but also provides food for all of these species directly through leaves, sap, and acorns or indirectly through the other animals it provides a habitat for.

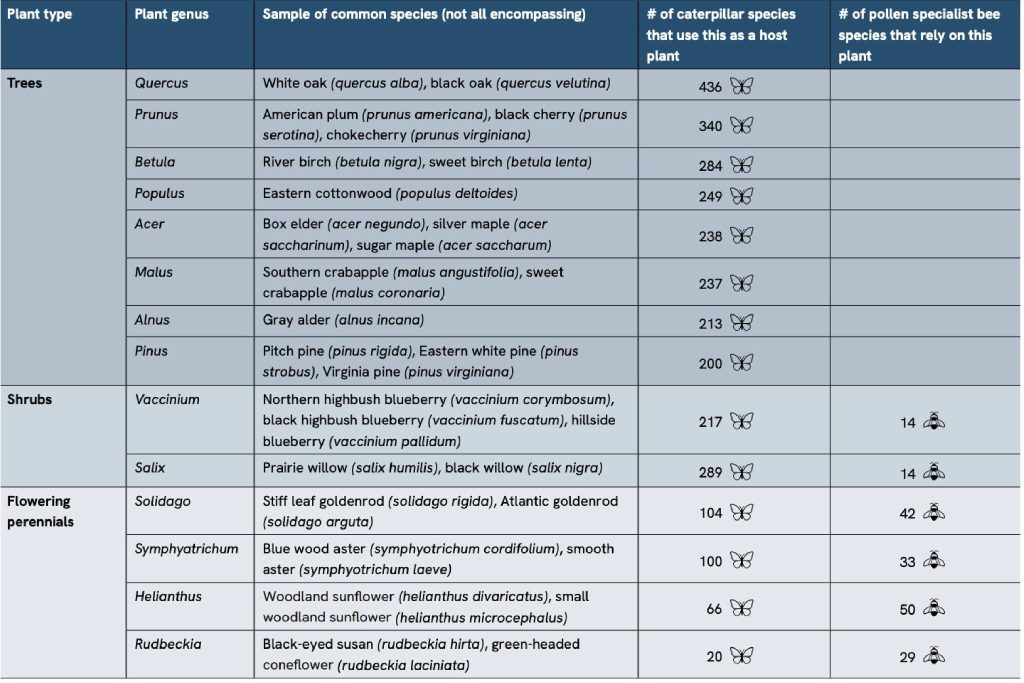

By changing the plants that form the foundation of the trophic pyramid, we change what animals can populate the area. For small-scale rewilding, you only need to build the base, and mobile species will naturally migrate, forming an ecosystem around that foundation; it is important to note, however, that the introduced base must match your ecological region. Your specific ecoregion can be found through tools such as the ecological zone map from Native Garden Designs (What’s My Ecoregion? – Native Garden Designs, 2025). As far as what to plant for our region here in the North East temperate area, we can look to the recommendations of Dr. Tallamy, a well-renowned American entomologist, ecologist, and conservationist at the University of Delaware known for his work on the interplay between native plants and wildlife. Tallamy’s list, provided through the National Wildlife Federation, focuses on regional native species that are known to attract a variety of insects but especially pollinators. Here Tallamy makes use of a mixture of trees (oak, pine, birch), shrubs (blueberries, prairie willow), and flowering perennials (woodland sunflower, stiff leaf goldenrod, blue wood aster).

These can be integrated into a preexisting garden if desired or preferably left to grow wild in order to provide food and shelter to a variety of essential pollinators, some of which may help attract birds. Another helpful aspect in small-scale rewilding is simply allowing your grass to grow out. Studies have shown that even a few extra inches in lawn grass length can be correlated with a notable increase in insect biodiversity, as many insects like to reside within taller grasses (Winkler et al., 2024).

Unwanted Species and What to Do About Them

Unfortunately, many of us are quite aware of the tendency for long grasses to attract bugs, including very unwanted species which can cause health concerns, such as ticks. Regrettably, this attraction of unwanted species alongside more desirable species, which lend an active service, such as pollinators like bees or helpful predators that aid in pest control, such as ladybugs and dragonflies, is unavoidable. This is a big turn-off for many people when it comes to rewilding this close to the home. No one wants a living space full of ticks, mosquitoes, ants, or other pest species, but unfortunately, this is a trade-off we have to make in order to support the species that do help us. Ants, ticks, mosquitoes, and all of these other kinds of pest bugs serve as valuable sources of food for birds and other more beneficial insects, and there is no way for us as individuals (the mosquito sterilization project is outside of our realm of control) to safely get rid of them without also harming the larger ecosystem as pesticides kill everything and forced introduction of predators can disrupt ecological balance (Tallamy, 2019). This situation is something we have to accept in order to serve the larger community that is Earth’s ecosystems. Thankfully, predation by avian and insect predators, which these species naturally attract, helps to control their populations in a healthy environment. If the presence of pest insects or damaging invasive species becomes too prevalent, direct action can be taken to try to combat them. Direct action against problematic species is difficult to recommend, however, due to the threat of compromising the integrity of the rewilding project as a conservation measure by again forcing human ideals onto the development and operation of nature. If it must be done, however, the best method for pest control is through natural means, namely the introduction of targeted predatory species; for example, if you have a drastic aphid problem, the introduction of ladybugs could be a useful measure in bringing down the population of a problem species. However, the aphid population will not be totally eradicated, nor should they be.

The introduction of other specialized predators can also be used to deal with invasive species, such as the introduction of parasitic scoliid wasps to curb the growth of Japanese beetle populations (Beneficial Insects for a Healthy Garden: A Visual Guide, 2024). Artificially introducing species to a new space can be dangerous, though, especially because it is incredibly difficult to predict how a change in one part of the ecosystem can cascade into a much larger change due to the sheer complexity of interactions that take place between species. Any kind of intervention along these lines should be avoided if possible and, if found to be absolutely necessary, carried out with the help of local ecology experts. Despite the dangers of reintroduction even with expert supervision, this approach is still vastly preferable to any kind of pesticide, which should be avoided at all costs due to issues with bioaccumulation of toxins and collateral damage to non-target species, as was the case with DDT in the 1950s-60s (Carson, 1962). But what about concerns around attracting larger animals like bears, skunks, or coyotes? To help ease the concern that this practice might lead to unwanted or dangerous animal encounters, it should be known that urban/suburban rewilding is inherently selective in the species it repopulates. This is due to the fragmented nature of habitats in the urban world, which makes migration of larger land animals physically difficult as they have to pass through busy roads, industrial areas, and more in order to move between habitats (Finnerty et al., 2025). Unfortunately, this same limitation, which helps minimize risk of human-animal encounters with larger animals, also limits the full functionality of the rewilded ecosystem which is why small-scale rewilding should be used in conjunction with other conservation efforts to be most effective.

Closing Remarks

Small-scale rewilding modifies the concept of green space in urban rewilding and expands its function to create viable habitat alongside human infrastructure by allowing well selected native species to grow wildly with minimal human intervention applied only when absolutely necessary to prevent further damage to the ecosystem of the rewilded area. This process can be augmented by the reintroduction of native non-plant species if migration of organisms through organic means is impeded by some obstacle or in emergency situations where an issue requires immediate resolution. Although the addition of artificially introduced animals opens up a variety of potential pitfalls if done improperly. Replacing conventional landscaping with native plant species, which have served ecological roles within their environment for countless centuries, is all it takes to begin to turn a human-centered space into something of conservational value (Tallamy, 2019). If everyone, who reasonably could, chose to adapt their lawn, roofspace, or garden boxes into something which serves a larger purpose than just decoration for human aesthetics through these methods, we could make a dent in the American biodiversity crisis.

References

Allen, I. (2016, December 16). The trouble with rewilding… – undisciplined environments. Undisciplinedenvironments.org. https://undisciplinedenvironments.org/2016/12/14/the-trouble-with-rewilding/

Beneficial Insects for a Healthy Garden: a Visual Guide. (2024, June 11). Monrovia.com. https://www.monrovia.com/be-inspired/beneficial-insects-for-a-healthy-garden.html

Carson, R. (1962). Silent Spring. Penguin Books.

Cowser, R., & Steward, N. R. (2023). Lawn Be Gone. Extension. https://extension.unh.edu/blog/2023/08/lawn-be-gone

Farquhar, B. (2023, June 22). Wolf reintroduction changes ecosystem in yellowstone. Yellowstone National Park. https://www.yellowstonepark.com/things-to-do/wildlife/wolf-reintroduction-changes-ecosystem/

Finnerty, P. B., Carthey, A. J. R., Banks, P. B., Brewster, R., Grueber, C. E., Houston, D., Martin, J. M., McManus, P., Roncolato, F., Lily, Wauchope, M., & Newsome, T. M. (2025). Urban rewilding to combat global biodiversity decline. BioScience. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biaf062

Gerretsen, I. (2025, October 20). “It was the start of a new movement”: The dutch rewilding project that took a dark turn. Bbc.com; BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20251016-the-dutch-rewilding-project-that-took-a-dark-turn

Missouri Department of Conservation. (2024). Why Should We Care about Birds? Missouri Department of Conservation. https://mdc.mo.gov/wildlife/birds-7/why-should-we-care-about-birds

Monks, K. (2022, November 22). Urban rewilding is bringing wildlife to the heart of cities. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/11/22/world/urban-rewilding-tiny-forest-cities-future-scn-spc-intl

Overview Ecosystem Services & Nature Based Solutions. (n.d.). Native Plant Conservation Campaign. https://nativeplantsocietyofus.org/ecosystem-services-resources/

Ripple, W. J., & Beschta, R. L. (2012). Trophic cascades in yellowstone: The first 15 years after wolf reintroduction. Biological Conservation, 145(1), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.005

Ripple, W. J., Beschta, R. L., Wolf, C., Painter, L. E., & Wirsing, A. J. (2025). The strength of the yellowstone trophic cascade after wolf reintroduction. Global Ecology and Conservation, 58, e03428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2025.e03428

Ritchie, H., Roser, M., & Spooner, F. (2021). Biodiversity. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/biodiversity

Rosenberg, K. V., Dokter, A. M., Blancher, P. J., Sauer, J. R., Smith, A. C., Smith, P. A., Stanton, J. C., Panjabi, A., Helft, L., Parr, M., & Marra, P. P. (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science, 366(6461), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1313

Standish, R. J., Hobbs, R. J., & Miller, J. R. (2012). Improving city life: options for ecological restoration in urban landscapes and how these might influence interactions between people and nature. Landscape Ecology, 28(6), 1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-012-9752-1

Steinberg, T. (2019). Down to earth : Nature’s role in american history. Oxford University Press. (Original work published 2002)

Svenning, J.-C. (2020). Rewilding should be central to global restoration efforts. One Earth, 3(6), 657–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.11.014

Tallamy, D. (n.d.). Top keystone plant genera in eastern temperate forests -ecoregion 8. https://www.nwf.org/-/media/Documents/PDFs/Garden-for-Wildlife/Keystone-Plants/NWF-GFW-keystone-plant-list-ecoregion-8-eastern-temperate-forests.pdf

Tallamy, D. W. (2019). Nature’s best hope : a new approach to conservation that starts in your yard. Timber Press.

Ten years of yellowstone wolves. (1995). https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/upload/YS_13_1_sm.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Török, P., Brudvig, L. A., Kollmann, J., Price, J., & Tóthmérész, B. (2021). The present and future of grassland restoration. Restoration Ecology, 29(S1). https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13378

Ulrich, J., & Sargent, R. D. (2024). Habitat Restorations in an Urban Landscape Rapidly Assemble Diverse Pollinator Communities That Persist. Ecology Letters, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.70037

What’s My Ecoregion? – Native Garden Designs. (2025, May 5). Native Garden Designs. https://nativegardendesigns.wildones.org/whats-my-ecoregion/

Wildlife and Biodiversity | NWF Native Plant Habitats. (2024). National Wildlife Federation. https://www.nwf.org/Native-Plant-Habitats/Impact/Wildlife-and-Biodiversity

Winkler, J., Pasternak, G., Sas, W., Hurajová, E., Koda, E., & Vaverková, M. D. (2024). Nature-Based management of lawns—enhancing biodiversity in urban green infrastructure. Applied Sciences, 14(5), 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14051705

WWF’s Living Planet Report Reveals Average Two-thirds Decline in Wildlife Populations Since 197. (2020). Panda.org. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?780191%2FLPR-2020=